Saga Pattern Deep Dive: When Choreography Beats Orchestration (And Vice Versa)

Your order service just charged a customer’s credit card, but the inventory service crashed mid-transaction. Now you have money without a shipment, an angry customer, and no clear path to recovery. The database team suggests wrapping everything in a distributed transaction, but you know that path leads to its own circle of hell—one where your entire system grinds to a halt waiting for locks that span three data centers.

This is the fundamental tension of distributed systems: you need consistency across service boundaries, but the traditional tools for achieving it become liabilities at scale. Two-phase commit, the textbook answer to distributed transactions, works beautifully in diagrams and disastrously in production. It assumes networks are reliable, coordinators never fail, and latency between services is negligible. Your infrastructure laughs at these assumptions.

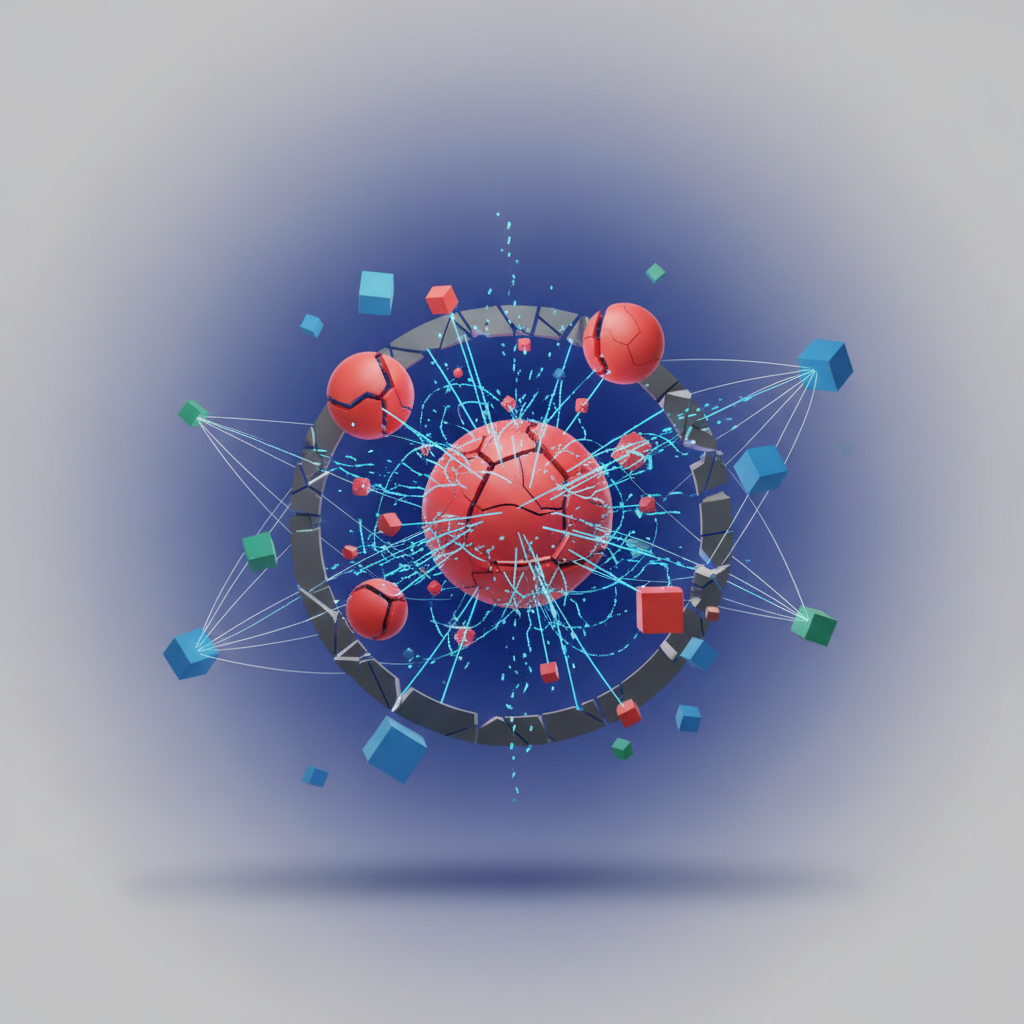

The saga pattern offers an escape from this trap. Instead of locking resources across services until everyone agrees to commit, sagas break transactions into a sequence of local operations, each with a corresponding compensation action that can undo its effects. When that inventory service crashes, the saga doesn’t leave your system in limbo—it triggers a refund to the customer’s card and logs the failure for retry.

But here’s where most engineering teams stumble: the saga pattern isn’t a single solution. It’s a choice between two fundamentally different coordination strategies—choreography and orchestration—and picking the wrong one creates problems just as painful as the distributed transactions you were trying to escape.

Before diving into that choice, it’s worth understanding exactly why the traditional approach fails so spectacularly when your services stop living on the same rack.

Why Two-Phase Commit Fails at Scale

Two-phase commit (2PC) served distributed databases well for decades. The protocol is elegant: a coordinator asks all participants to prepare, waits for unanimous agreement, then issues a global commit. Every computer science textbook covers it. Every enterprise database implements it.

And it falls apart the moment you try to run it across microservices.

The Distributed Lock Problem

2PC requires all participating services to hold locks on their resources during the entire transaction. When your order service calls inventory, payment, and shipping services, each one locks its relevant database rows and waits. The coordinator collects votes. The services keep waiting. The coordinator issues the final commit. Only then do locks release.

In a monolith hitting a single database, this coordination happens in milliseconds. In a distributed system spanning multiple services, networks, and data centers, that “brief” lock duration stretches. A payment service responding slowly means inventory rows stay locked. A network hiccup between availability zones means shipping data remains inaccessible.

The result is lock contention that scales with your transaction complexity. Add a fifth service to your transaction, and you’ve added another potential bottleneck. Your system’s throughput becomes gated by your slowest participant.

Coordinator Failure Cascades

The 2PC coordinator represents a brutal single point of failure. If the coordinator crashes after sending prepare messages but before sending commit decisions, participating services enter a blocked state. They’ve promised to commit. They’re holding locks. They cannot proceed without instructions that will never arrive.

This isn’t a theoretical concern. Network partitions happen. Containers get evicted. Nodes restart. When they do, services holding 2PC locks must either wait for coordinator recovery or risk data inconsistency by timing out unilaterally.

The timeout problem compounds across availability zones. Set timeouts too short, and normal cross-zone latency triggers false failures. Set them too long, and a single stalled coordinator blocks transactions for minutes. There’s no good answer within the 2PC model.

Latency Compounds

Cross-zone network calls typically add 1-5ms of latency. A 2PC transaction touching four services across two availability zones requires at minimum eight network round trips: prepare requests, prepare responses, commit requests, commit responses. Under load, these calls queue behind each other. A transaction that takes 50ms locally balloons to 500ms or more in production.

Microservices architectures need a different approach—one that embraces eventual consistency rather than fighting it. The saga pattern provides exactly that: a way to maintain data integrity across services without distributed locks or coordinators holding the system hostage.

Saga Pattern Fundamentals: Local Transactions Plus Compensations

The saga pattern emerged from a 1987 paper by Hector Garcia-Molina and Kenneth Salem, addressing long-lived transactions that couldn’t hold database locks for extended periods. Decades later, this same pattern solves distributed transaction coordination across microservices—not by attempting global atomicity, but by embracing a fundamentally different consistency model.

Breaking ACID at Service Boundaries

Traditional ACID transactions guarantee that a series of operations either all succeed or all fail, with the database handling rollback automatically. In a distributed system, each service owns its database, making cross-service ACID transactions impossible without distributed locks—which, as we established, don’t scale.

Sagas decompose a distributed transaction into a sequence of local transactions, each scoped to a single service. When you process an order, instead of one atomic operation spanning inventory, payments, and shipping, you execute three separate local transactions:

- Inventory service reserves items (local commit)

- Payment service charges the customer (local commit)

- Shipping service schedules delivery (local commit)

Each step commits immediately to its local database. No locks span services. No coordinator holds resources waiting for votes. The saga progresses through independent, locally-atomic operations.

Compensating Transactions: Semantic Rollback

The obvious question: what happens when step three fails after steps one and two have already committed?

This is where compensating transactions enter the picture. A compensating transaction is a semantic inverse—an operation that undoes the business effect of a previously committed transaction. If payment succeeds but shipping fails, the saga executes compensations in reverse order:

- Payment service issues a refund (compensates for charge)

- Inventory service releases the reservation (compensates for reserve)

Compensating transactions aren’t true rollbacks. The original transactions remain in the database history. Instead, compensations apply corrective operations that restore business state to its pre-saga condition. A refund isn’t deleting a payment record; it’s creating a new credit transaction.

💡 Pro Tip: Not every operation has a clean compensation. Sending an email can’t be unsent. Design your saga steps so irreversible actions occur last, after all fallible operations complete.

The Eventual Consistency Contract

Sagas trade strong consistency for availability and partition tolerance. Between the first local commit and the final commit (or final compensation), the system exists in an intermediate state. Inventory shows reserved items that might never ship. Payment records exist for orders that might fail.

Engineers must design for this reality. Read operations might observe partial saga state. Business logic must tolerate temporarily inconsistent views. Clients need appropriate expectations—an order acknowledgment means “processing started,” not “transaction complete.”

This isn’t a defect to engineer around; it’s the fundamental trade-off that enables distributed systems to function at scale.

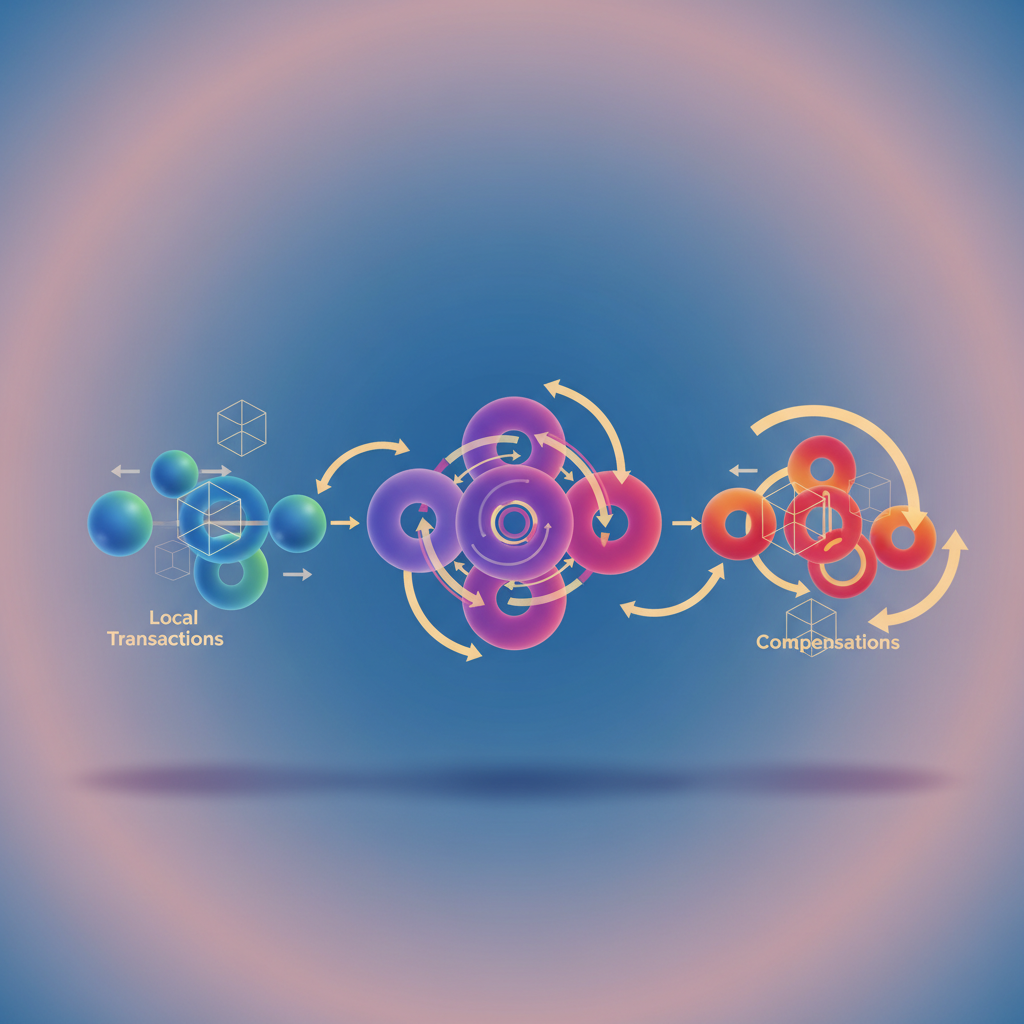

With the core mental model established—local transactions moving forward, compensations enabling rollback—the next question becomes implementation. Choreography and orchestration represent two distinct approaches to coordinating saga execution, each with significant architectural implications.

Choreography Implementation: Event-Driven Sagas

In choreography-based sagas, each service owns its decisions. Services publish domain events when their local transactions complete, and other services react to those events autonomously. No central coordinator exists—the saga emerges from the collective behavior of independent services responding to events.

This approach mirrors how real organizations work: the warehouse doesn’t wait for a manager to tell it when to ship. It reacts when it sees a “payment confirmed” signal and publishes its own “shipment dispatched” event for others to consume. The choreography pattern distributes saga logic across services, embedding the workflow knowledge directly into each participant rather than centralizing it.

Building an Order Saga with Redis Pub/Sub

Let’s implement a three-service order saga: OrderService creates orders, PaymentService processes payments, and InventoryService reserves stock. Each service publishes events and subscribes to events it cares about. Redis Pub/Sub provides the messaging backbone—lightweight, fast, and sufficient for many real-time event routing scenarios.

First, we define our event types and shared event structure:

export interface SagaEvent { sagaId: string; timestamp: number; payload: Record<string, unknown>;}

export type EventType = | 'ORDER_CREATED' | 'PAYMENT_COMPLETED' | 'PAYMENT_FAILED' | 'INVENTORY_RESERVED' | 'INVENTORY_FAILED' | 'ORDER_COMPLETED' | 'ORDER_CANCELLED';The sagaId serves as our correlation identifier, threading through every event in a saga instance. This allows services to track which local transactions belong to which distributed workflow—critical for both observability and compensation logic.

import Redis from 'ioredis';

export class EventBus { private publisher: Redis; private subscriber: Redis;

constructor(redisUrl: string) { this.publisher = new Redis(redisUrl); this.subscriber = new Redis(redisUrl); }

async publish(eventType: string, event: SagaEvent): Promise<void> { await this.publisher.publish(eventType, JSON.stringify(event)); }

subscribe(eventType: string, handler: (event: SagaEvent) => Promise<void>): void { this.subscriber.subscribe(eventType); this.subscriber.on('message', async (channel, message) => { if (channel === eventType) { await handler(JSON.parse(message)); } }); }}Note that we use separate Redis connections for publishing and subscribing. Redis requires this separation—a connection in subscriber mode cannot issue publish commands. This is a common gotcha when first implementing Redis Pub/Sub.

Each service maintains its own state and reacts to relevant events:

export class PaymentService { constructor(private eventBus: EventBus, private db: Database) { this.eventBus.subscribe('ORDER_CREATED', this.handleOrderCreated.bind(this)); this.eventBus.subscribe('INVENTORY_FAILED', this.handleInventoryFailed.bind(this)); }

private async handleOrderCreated(event: SagaEvent): Promise<void> { const { sagaId, payload } = event; const { orderId, amount, customerId } = payload as OrderPayload;

try { await this.db.transaction(async (tx) => { await tx.insert('payments', { sagaId, orderId, amount, status: 'completed' }); await tx.update('accounts', { balance: sql`balance - ${amount}` }, { customerId }); });

await this.eventBus.publish('PAYMENT_COMPLETED', { sagaId, timestamp: Date.now(), payload: { orderId, amount } }); } catch (error) { await this.eventBus.publish('PAYMENT_FAILED', { sagaId, timestamp: Date.now(), payload: { orderId, reason: error.message } }); } }

private async handleInventoryFailed(event: SagaEvent): Promise<void> { // Compensating transaction: refund the payment const payment = await this.db.findOne('payments', { sagaId: event.sagaId }); if (payment && payment.status === 'completed') { await this.db.transaction(async (tx) => { await tx.update('payments', { status: 'refunded' }, { sagaId: event.sagaId }); await tx.update('accounts', { balance: sql`balance + ${payment.amount}` }, { customerId: payment.customerId }); }); } }}Compensation Through Failure Events

When InventoryService fails to reserve stock, it publishes INVENTORY_FAILED. PaymentService listens for this event and executes its compensating transaction—refunding the charge. The OrderService similarly listens and marks the order as cancelled. Each service knows how to undo its own work; it just needs to be told when.

The compensation chain propagates backward through failure events:

private async handlePaymentCompleted(event: SagaEvent): Promise<void> { const { sagaId, payload } = event;

try { const reserved = await this.reserveStock(payload.orderId); if (!reserved) { throw new Error('Insufficient inventory'); } await this.eventBus.publish('INVENTORY_RESERVED', { sagaId, timestamp: Date.now(), payload }); } catch (error) { // This triggers compensation in PaymentService await this.eventBus.publish('INVENTORY_FAILED', { sagaId, timestamp: Date.now(), payload: { orderId: payload.orderId, reason: error.message } }); }}💡 Pro Tip: Store the

sagaIdwith every local transaction record. When compensation events arrive, you need to find and reverse the exact transaction associated with that saga instance. Without this correlation ID persisted in your database, compensation becomes guesswork.

Tradeoffs and Considerations

This decentralized model works well when services have clear domain boundaries and the saga involves three to five steps. Each service remains autonomous—it can be deployed, scaled, and tested independently. Teams can modify their service’s saga participation without coordinating deployments across the organization.

The tradeoff is visibility: understanding what happened in a saga requires correlating events across multiple service logs. Debugging a failed order means tracing the sagaId through OrderService, PaymentService, and InventoryService logs—potentially across different logging systems. Invest in distributed tracing infrastructure before adopting choreography at scale.

Another consideration: Redis Pub/Sub delivers messages only to currently connected subscribers. If a service restarts and misses an event, that event is lost. For production systems, consider Redis Streams or a dedicated message broker like Kafka that provides message persistence and replay capabilities.

When saga complexity grows beyond a handful of services, or when you need explicit control over step ordering and retry policies, a centralized coordinator becomes attractive. Let’s examine that approach next.

Orchestration Implementation: Centralized Saga Coordinator

Orchestration flips the choreography model on its head. Instead of services reacting to events and implicitly knowing their role in a transaction, a dedicated orchestrator explicitly directs each step. This central coordinator maintains the saga’s state, issues commands to participating services, and handles responses—making the entire transaction flow visible in a single location.

The orchestrator pattern treats a saga as a state machine. Each state represents a step in the distributed transaction, and transitions occur based on service responses. When a step fails, the orchestrator knows exactly which compensating actions to trigger because it maintains the complete execution history. This explicit control flow eliminates the implicit coupling that can make choreographed sagas difficult to reason about as they grow in complexity.

Saga State Machine with PostgreSQL

Durability is non-negotiable for saga orchestration. If your orchestrator crashes mid-transaction, it must recover and continue from exactly where it left off. PostgreSQL provides the transactional guarantees needed to persist saga state reliably. The database becomes your single source of truth—every state transition is recorded atomically, ensuring that even catastrophic failures can’t leave a saga in an ambiguous state.

The schema design matters here. You need enough information to reconstruct the saga’s context after a restart, including which steps completed successfully, what data each step returned, and the original payload that initiated the transaction.

interface SagaState { sagaId: string; type: 'ORDER_SAGA'; currentStep: number; status: 'RUNNING' | 'COMPLETED' | 'COMPENSATING' | 'FAILED'; payload: Record<string, unknown>; completedSteps: string[]; createdAt: Date; updatedAt: Date;}

interface SagaStep { name: string; execute: (payload: Record<string, unknown>) => Promise<StepResult>; compensate: (payload: Record<string, unknown>) => Promise<void>;}

class OrderSagaOrchestrator { private steps: SagaStep[] = [ { name: 'reserveInventory', execute: this.reserveInventory, compensate: this.releaseInventory }, { name: 'processPayment', execute: this.processPayment, compensate: this.refundPayment }, { name: 'createShipment', execute: this.createShipment, compensate: this.cancelShipment }, ];

async start(orderId: string, payload: Record<string, unknown>): Promise<void> { const sagaId = crypto.randomUUID();

await this.db.query(` INSERT INTO sagas (saga_id, type, current_step, status, payload, completed_steps) VALUES ($1, 'ORDER_SAGA', 0, 'RUNNING', $2, '{}') `, [sagaId, JSON.stringify(payload)]);

await this.executeNextStep(sagaId); }

private async executeNextStep(sagaId: string): Promise<void> { const saga = await this.loadSaga(sagaId);

if (saga.currentStep >= this.steps.length) { await this.completeSaga(sagaId); return; }

const step = this.steps[saga.currentStep];

try { const result = await step.execute(saga.payload);

await this.db.query(` UPDATE sagas SET current_step = current_step + 1, completed_steps = completed_steps || $2, payload = payload || $3, updated_at = NOW() WHERE saga_id = $1 `, [sagaId, JSON.stringify([step.name]), JSON.stringify(result.data)]);

await this.executeNextStep(sagaId); } catch (error) { await this.startCompensation(sagaId, error); } }}Command-Based Service Invocation

Unlike choreography where services publish events to whoever might be listening, orchestration uses explicit commands. The orchestrator sends targeted requests to specific services and awaits their responses. This request-response model creates a clear contract between the orchestrator and each participating service—the service knows exactly what action to perform and what response format the orchestrator expects.

The command bus abstraction decouples the orchestrator from transport concerns. Whether you’re using HTTP, gRPC, or message queues, the orchestrator logic remains the same. Each command carries a correlation ID that ties the request back to the originating saga, enabling proper response routing even in asynchronous scenarios.

class OrderSagaOrchestrator { private async reserveInventory(payload: Record<string, unknown>): Promise<StepResult> { const response = await this.commandBus.send('inventory-service', { type: 'RESERVE_INVENTORY', correlationId: payload.sagaId, data: { items: payload.items, orderId: payload.orderId } });

if (!response.success) { throw new StepFailedError('Inventory reservation failed', response.reason); }

return { data: { reservationId: response.reservationId } }; }

private async startCompensation(sagaId: string, originalError: Error): Promise<void> { await this.db.query(` UPDATE sagas SET status = 'COMPENSATING' WHERE saga_id = $1 `, [sagaId]);

const saga = await this.loadSaga(sagaId);

// Execute compensations in reverse order for (let i = saga.completedSteps.length - 1; i >= 0; i--) { const stepName = saga.completedSteps[i]; const step = this.steps.find(s => s.name === stepName); await step.compensate(saga.payload); }

await this.db.query(` UPDATE sagas SET status = 'FAILED' WHERE saga_id = $1 `, [sagaId]); }}💡 Pro Tip: Store the saga definition version alongside the state. When you deploy orchestrator changes, in-flight sagas can continue executing under their original step definitions, preventing mid-transaction breaking changes.

The command-response pattern provides explicit acknowledgment of each step’s completion. Services don’t need awareness of the broader saga—they simply execute commands and return results. This isolation means you can modify the saga flow without touching participating services, a significant advantage when evolving complex business processes.

Orchestration shines when you need visibility into transaction state. A single query against your sagas table reveals every in-flight order, its current step, and any compensation in progress. Operations teams can monitor saga health, identify bottlenecks at specific steps, and even manually intervene when necessary. This observability comes built-in rather than requiring reconstruction from distributed event streams.

The tradeoff is clear: the orchestrator becomes a coordination point that must be highly available. But this centralization introduces questions about failure handling that apply to both patterns—idempotency, retries, and what happens when compensations themselves fail.

The Decision Framework: Choreography vs Orchestration

Choosing between choreography and orchestration isn’t a technical decision alone—it’s an organizational one. The right pattern depends on team structure, operational maturity, and the specific complexity profile of your transaction flows.

Team Autonomy vs Operational Visibility

Choreography maximizes team independence. Each service owns its event handlers, compensation logic, and deployment schedule. Teams can evolve their piece of the saga without coordinating releases. This autonomy comes at a cost: no single place shows the current state of any transaction.

Orchestration inverts this trade-off. A central coordinator provides a clear execution log, explicit state management, and simplified debugging. But that coordinator becomes a shared dependency. Changes to saga flow require updates to the orchestrator, creating coordination overhead between teams.

Consider your organization’s priorities:

| Factor | Favors Choreography | Favors Orchestration |

|---|---|---|

| Team structure | Independent, loosely coupled teams | Centralized platform team |

| Debugging needs | Teams debug their own services | Ops team needs transaction visibility |

| Change velocity | Services evolve independently | Saga logic changes frequently |

| Failure handling | Each service handles its own retry logic | Centralized retry and timeout policies |

The Complexity Threshold

Choreography scales poorly with saga complexity. Three services exchanging events remains manageable. Seven services with conditional branches, parallel executions, and timeout requirements becomes a distributed state machine that exists only in the collective behavior of independent components.

A useful heuristic: if you need to draw the saga flow diagram to understand what happens during failures, choreography has exceeded its maintainability threshold. When compensations depend on which steps completed, when branches converge, or when timeouts trigger different paths—these scenarios demand the explicit control flow that orchestration provides.

💡 Pro Tip: Count the number of compensation paths in your saga. If it exceeds the number of forward steps, orchestration will save debugging time.

Hybrid Approaches

Production systems rarely use pure patterns. A common hybrid: orchestrate the critical path while choreographing peripheral concerns. The order saga orchestrator manages payment, inventory, and shipping coordination. Notification services, analytics events, and cache invalidations subscribe to saga completion events without participating in the orchestrated flow.

Another pattern: choreography between bounded contexts, orchestration within them. The Order context and Fulfillment context communicate via events. Inside each context, an orchestrator manages multi-step workflows.

Whatever pattern you choose, failure handling remains the hard problem. Idempotent operations, intelligent retries, and dead letter queues form the foundation that makes either approach production-ready.

Handling Saga Failures: Idempotency, Retries, and Dead Letters

Distributed systems fail in creative ways. Network partitions, service crashes, and duplicate message deliveries are not edge cases—they are operational reality. Your saga implementation needs to handle failures gracefully, recover automatically when possible, and escalate to human operators when automatic recovery fails. The strategies outlined here form the foundation of resilient saga orchestration.

Designing Idempotent Compensating Transactions

Every saga participant must handle receiving the same message multiple times. A compensation that refunds a payment should produce the same result whether executed once or ten times. The key is tracking transaction identifiers and checking for prior execution before taking action.

Idempotency requires more than simple deduplication. You need to distinguish between a compensation that completed successfully, one that failed and should be retried, and one that partially executed before a crash. Each scenario demands different handling logic.

interface CompensationRecord { sagaId: string; stepId: string; completedAt: Date; result: 'success' | 'failed';}

class IdempotentCompensationHandler { constructor(private compensationStore: CompensationStore) {}

async executeCompensation( sagaId: string, stepId: string, compensate: () => Promise<void> ): Promise<void> { const existing = await this.compensationStore.find(sagaId, stepId);

if (existing?.result === 'success') { console.log(`Compensation ${sagaId}:${stepId} already executed, skipping`); return; }

try { await compensate(); await this.compensationStore.save({ sagaId, stepId, completedAt: new Date(), result: 'success' }); } catch (error) { await this.compensationStore.save({ sagaId, stepId, completedAt: new Date(), result: 'failed' }); throw error; } }}Store compensation records in the same database transaction as the compensating action itself. This guarantees that your idempotency check reflects the actual system state, even after crashes or network failures. Without this transactional guarantee, you risk scenarios where the compensation executes but the record fails to persist, leading to duplicate compensations on retry.

Retry Strategies That Prevent Infinite Loops

Naive retry logic creates dangerous feedback loops. A service that immediately retries failed operations can amplify transient failures into system-wide outages. Exponential backoff with jitter spreads retry attempts over time and prevents thundering herd problems when multiple saga instances fail simultaneously.

The circuit breaker pattern provides an additional layer of protection. When a downstream service experiences sustained failures, continuing to send requests wastes resources and delays recovery. Opening the circuit allows the failing service time to recover while your saga can fail fast and potentially route to alternative handling paths.

interface RetryConfig { maxAttempts: number; baseDelayMs: number; maxDelayMs: number; circuitBreakerThreshold: number;}

class SagaRetryHandler { private consecutiveFailures = 0; private circuitOpen = false;

constructor(private config: RetryConfig) {}

async executeWithRetry<T>(operation: () => Promise<T>): Promise<T> { if (this.circuitOpen) { throw new Error('Circuit breaker open, operation rejected'); }

for (let attempt = 1; attempt <= this.config.maxAttempts; attempt++) { try { const result = await operation(); this.consecutiveFailures = 0; return result; } catch (error) { this.consecutiveFailures++;

if (this.consecutiveFailures >= this.config.circuitBreakerThreshold) { this.circuitOpen = true; setTimeout(() => this.circuitOpen = false, 30000); }

if (attempt === this.config.maxAttempts) throw error;

const delay = Math.min( this.config.baseDelayMs * Math.pow(2, attempt - 1) + Math.random() * 1000, this.config.maxDelayMs ); await this.sleep(delay); } } throw new Error('Retry exhausted'); }

private sleep(ms: number): Promise<void> { return new Promise(resolve => setTimeout(resolve, ms)); }}💡 Pro Tip: Set your circuit breaker threshold based on your downstream service’s recovery time. Opening the circuit too aggressively causes unnecessary failures; opening it too slowly allows cascading failures to propagate.

Dead Letter Queues for Manual Intervention

Some failures resist automatic recovery. A compensating transaction that depends on an external service experiencing extended downtime, or a saga with corrupted state, requires human intervention. Dead letter queues capture these stuck sagas with full context for operators to diagnose and resolve the underlying issues.

Route messages to the dead letter queue after exhausting retries. Include the original message, error details, saga state, and a complete history of retry attempts. This context proves invaluable when operators need to understand why automatic recovery failed. Build alerting that notifies on-call engineers when messages accumulate, and tooling that allows operators to inspect, modify, and replay failed sagas.

Consider implementing tiered dead letter handling. Some failures may be recoverable after a cooling-off period—a dead letter processor that periodically retries messages can resolve transient issues without human involvement. Reserve immediate alerting for failures that persist beyond this automated recovery window.

The dead letter queue is your safety net, not your primary error handling strategy. If more than 1% of your sagas end up in the dead letter queue, you have a systemic problem that requires architectural attention rather than manual intervention. Monitor dead letter queue depth as a key operational metric and investigate patterns in the types of failures that accumulate there.

With robust failure handling in place, you need visibility into saga execution patterns and the ability to verify your implementation behaves correctly under failure conditions.

Production Considerations: Observability and Testing

Sagas span multiple services, databases, and time intervals. Without proper observability, debugging a failed saga becomes archaeology—sifting through disconnected logs hoping to reconstruct what happened. Production-ready sagas require intentional instrumentation and testing strategies.

Correlation IDs: Your Debugging Lifeline

Every saga execution needs a unique correlation ID propagated through all participating services. This ID travels with every event, command, and compensation action. When a payment fails at step four of a five-step saga, you need to instantly pull every log entry, metric, and trace associated with that specific execution.

Generate the correlation ID at saga initiation and include it in message headers, structured logs, and distributed traces. In orchestrated sagas, the coordinator naturally owns this ID. In choreographed sagas, the initiating event carries it forward. Either way, enforce correlation ID propagation as a non-negotiable requirement—services that drop this context become debugging black holes.

Testing Strategies That Reflect Reality

Unit test each compensation action in isolation. Verify that compensations are truly idempotent by executing them multiple times against the same state. A compensation that fails on retry defeats the entire saga guarantee.

Integration testing requires simulating failure at each step. If your saga has five steps, you need test scenarios where steps two, three, four, and five fail independently. Verify that compensations execute in the correct reverse order and that the system reaches a consistent state.

💡 Pro Tip: Use chaos engineering principles in staging environments. Inject failures randomly into saga steps and verify your monitoring alerts fire before compensation timeouts expire.

Metrics That Drive Operational Decisions

Track three categories of saga metrics: duration percentiles (p50, p95, p99), failure rates per saga type, and compensation frequency. Duration spikes indicate downstream service degradation. Rising compensation rates signal integration problems or data quality issues requiring investigation.

Alert on compensation frequency, not just saga failures. A saga that consistently succeeds after compensating the first three steps represents wasted compute and degraded user experience—even though it technically “works.”

These observability foundations transform sagas from distributed mysteries into debuggable, measurable workflows that your on-call engineers can actually troubleshoot at 3 AM.

Key Takeaways

- Start with choreography for simple flows under 4 steps, switch to orchestration when you need visibility into saga state or have complex branching logic

- Design every saga step with its compensating transaction first—if you cannot define the undo, you cannot safely include the step

- Implement idempotency keys in all saga participants before going to production to prevent duplicate processing during retries

- Add correlation IDs from day one and log saga state transitions to enable debugging of distributed failures