From Airflow Frustration to Dagster Assets: A Migration Story

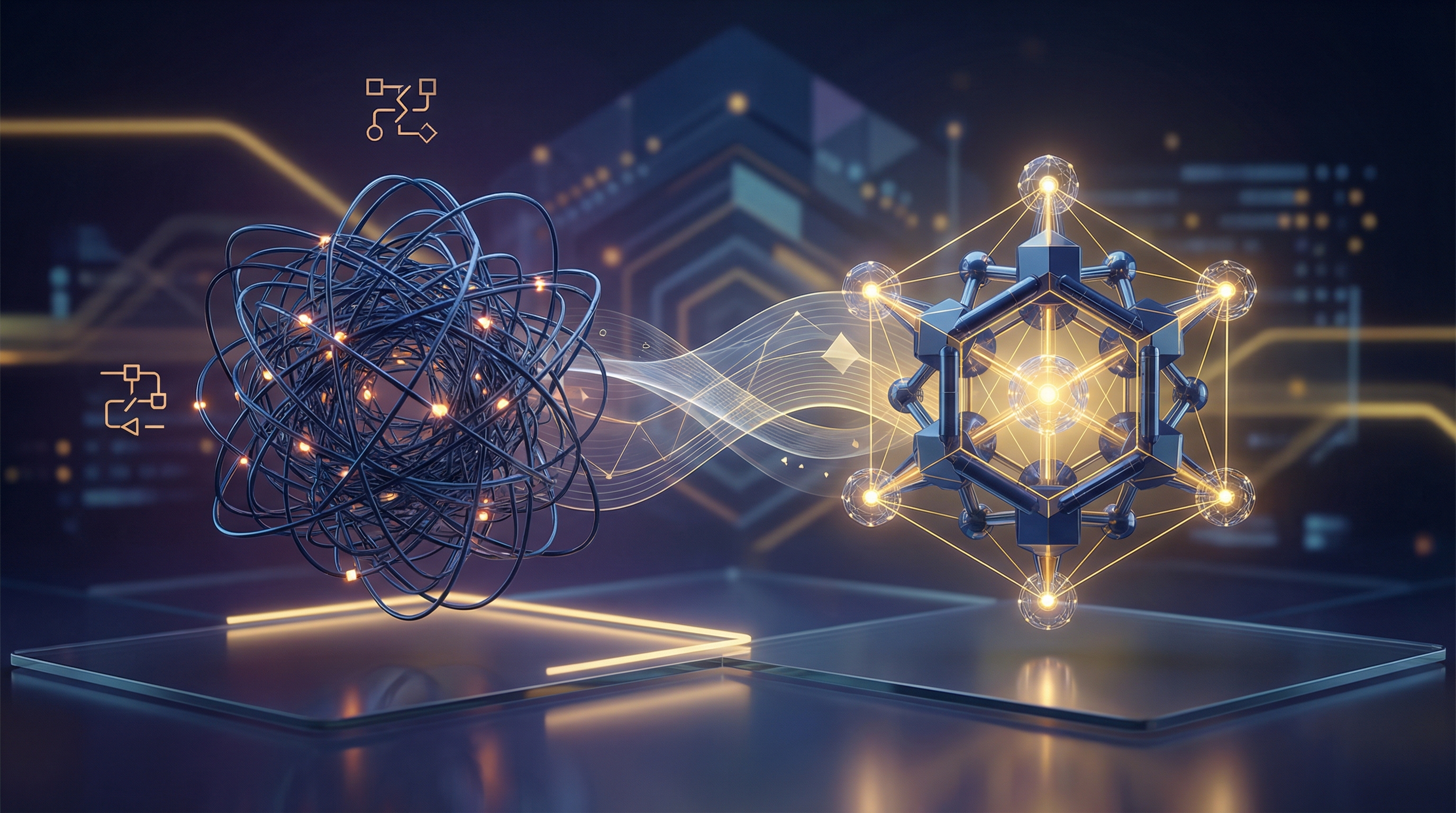

Your Airflow DAGs have become a tangled mess of task dependencies, and debugging a failed pipeline at 3 AM means tracing through dozens of operator logs to find which upstream task produced bad data. Dagster’s asset-centric approach offers a fundamentally different mental model—one where you reason about data products rather than task execution order.

This guide walks through the paradigm shift from task-based to asset-based orchestration, builds a complete Dagster pipeline from scratch, and provides a practical migration strategy for teams running Airflow in production.

The Task-Centric Trap: Why Your DAGs Are Hard to Debug

Traditional orchestration tools like Airflow organize work around tasks—discrete units of computation that execute in a defined order. You build DAGs by chaining operators together, specifying that Task B runs after Task A, Task C runs after Task B, and so on. This approach works well for simple workflows but creates significant maintenance burden as pipelines grow.

The fundamental problem is that task-based orchestration focuses on execution order rather than data lineage. When a downstream report shows incorrect numbers, you need to mentally reconstruct which tasks produced which intermediate datasets, then trace backward through the dependency chain to find where corruption entered the system. Operator logs tell you that tasks succeeded or failed, but they rarely capture the semantic meaning of what data was produced. A task can complete successfully while producing completely wrong output—the orchestrator has no way to know the difference.

Testing becomes equally challenging. To unit test a single Airflow operator in isolation, you need to mock the XCom values from upstream tasks, the connections to external systems, and often the Airflow context itself. The setup code for a single test frequently exceeds the length of the operator being tested. Most teams give up on comprehensive testing and rely on end-to-end integration tests that run the entire DAG against staging data. These tests are slow, flaky, and provide limited visibility into which specific transformation introduced a bug.

Schema evolution compounds these difficulties. When you change the output format of an upstream task—adding a column, renaming a field, changing a data type—downstream tasks may silently consume the altered data without validation. The failure surfaces far from its origin, perhaps days later when an analyst notices that a dashboard metric shifted unexpectedly. By then, the root cause is buried under layers of subsequent processing, and the engineer who made the change has long since moved on to other work.

Consider the common pattern of a DAG that extracts data from an API, loads it into a staging table, transforms it through several intermediate tables, and finally populates an analytics view. Each task in this chain has implicit contracts with its neighbors: the extractor assumes the API returns a specific schema, the loader assumes the extractor produced valid JSON, each transformer assumes specific columns exist in its input table. None of these contracts are explicit in the code, and violating them produces cryptic SQL errors rather than clear validation failures.

The cognitive load increases with scale. A mature data platform might have hundreds of DAGs containing thousands of tasks. Understanding the relationship between a raw event stream and a business metric requires spelunking through multiple repositories, tracing XCom dependencies, and building a mental map that exists nowhere in the codebase. New team members face weeks of archaeology before they can confidently modify existing workflows.

Cross-DAG dependencies introduce another layer of complexity. When DAG A produces data that DAG B consumes, you need external mechanisms—sensors, trigger rules, or database flags—to coordinate execution. These coordination mechanisms live outside both DAGs, making the dependency invisible to anyone reading either codebase in isolation.

Dagster addresses these problems by inverting the primary abstraction. Instead of defining tasks that happen to produce data, you define data assets that happen to require computation. This inversion has profound implications for debugging, testing, and team collaboration.

Software-Defined Assets: Dagster’s Core Mental Model

Dagster’s asset-centric model treats data products as first-class citizens. An asset represents something valuable that your pipeline produces and maintains: a database table, a machine learning model, a file in cloud storage, a cached API response. The computation that produces an asset is secondary to the asset itself. This shift in emphasis changes how you think about, build, and maintain data pipelines.

import dagster as dg

@dg.assetdef daily_active_users() -> int: """Count of unique users active in the past 24 hours.""" # Query your analytics database return 42_000This simple example already demonstrates the shift in thinking. The function name daily_active_users is the asset’s identity—it persists across code changes and serves as the stable reference point for this piece of data. The return type annotation documents what kind of data this asset produces, enabling Dagster to provide type checking and serialization. The docstring provides human-readable context that appears in Dagster’s UI, serving as living documentation that stays synchronized with the code. The implementation details—how you count users—are encapsulated within the function body and can change without affecting downstream consumers.

Dependencies between assets are declared explicitly by referencing upstream assets as function parameters:

import dagster as dgimport pandas as pd

@dg.assetdef raw_events() -> pd.DataFrame: """Raw event stream from the application database.""" return pd.DataFrame({ "user_id": [1, 2, 1, 3, 2], "event_type": ["login", "purchase", "logout", "login", "purchase"], "timestamp": pd.date_range("2026-02-09", periods=5, freq="h") })

@dg.assetdef user_session_summary(raw_events: pd.DataFrame) -> pd.DataFrame: """Aggregated session metrics per user.""" return raw_events.groupby("user_id").agg( total_events=("event_type", "count"), first_event=("timestamp", "min"), last_event=("timestamp", "max") ).reset_index()The user_session_summary asset declares its dependency on raw_events through its function signature. Dagster automatically infers that raw_events must be materialized before user_session_summary. No manual dependency specification required. This pattern scales naturally—you can have dozens of upstream dependencies, and the relationship remains clear from the function signature alone.

The distinction between materialization and execution is subtle but crucial. In Airflow, you run tasks. In Dagster, you materialize assets. Running a task is about execution—did the code complete without errors? Materializing an asset is about data—does this asset now exist in its storage location with fresh data? The Dagster UI surfaces this difference prominently, showing when each asset was last materialized and whether it needs updating based on upstream changes.

This semantic difference enables powerful features. Dagster can answer questions that Airflow cannot: “When was this data last updated?” “Which downstream assets depend on this one?” “If I change this asset, what else needs to be recomputed?” These questions have first-class answers in Dagster because assets are the primary abstraction, not an afterthought.

The asset graph provides automatic dependency resolution that goes beyond simple parent-child relationships. When you request materialization of a downstream asset, Dagster examines the entire graph to determine which upstream assets need materialization first. If raw_events was materialized yesterday but user_session_summary was never materialized, Dagster knows to materialize only user_session_summary. If both are stale, it materializes them in the correct order. This intelligent scheduling reduces unnecessary computation and simplifies operational reasoning.

Pro Tip: Think of assets as nouns (the data you want) rather than verbs (the work to do). Name them after what they represent, not what they compute. Good asset names read like entries in a data catalog:

daily_sales_summary,customer_lifetime_value,product_inventory_snapshot.

This mental model simplifies debugging dramatically. When a metric looks wrong, you navigate to that metric’s asset in the UI, examine its most recent materialization, and inspect the upstream assets that fed into it. The lineage is explicit in the code and visible in the UI. No mental reconstruction required. You can see exactly what data flowed through each step and when it was last computed.

Building Your First Asset Pipeline: From Raw Data to Analytics

A production Dagster project follows conventions that enable tooling and team collaboration. The standard structure places asset definitions in a definitions.py file within your project package. This file serves as the single entry point that Dagster loads, making it easy to understand what your pipeline contains without hunting through multiple files:

my_pipeline/├── my_pipeline/│ ├── __init__.py│ ├── definitions.py│ └── assets/│ ├── __init__.py│ ├── ingestion.py│ └── analytics.py├── pyproject.toml└── tests/The definitions.py file serves as the entry point that Dagster loads. It exports a Definitions object containing all assets, resources, schedules, and sensors. This centralized registry makes it straightforward to understand everything your pipeline contains:

import dagster as dgfrom my_pipeline.assets import ingestion, analytics

defs = dg.Definitions( assets=[ *dg.load_assets_from_modules([ingestion, analytics]) ])The load_assets_from_modules function discovers all assets decorated with @dg.asset within the specified modules. This convention-over-configuration approach means you can add new assets simply by defining them—no registration boilerplate required.

Here is a complete multi-asset pipeline that demonstrates realistic data transformation patterns. The pipeline ingests data from an external API, normalizes it into a structured format, and produces analytics-ready aggregations. Each asset has a single responsibility, making the pipeline easy to understand and test:

import dagster as dgimport pandas as pdimport requestsfrom datetime import datetime

@dg.asset( group_name="ingestion", kinds={"python", "api"})def raw_weather_data() -> pd.DataFrame: """Fetches weather data from external API for major cities.

This asset serves as the entry point for external data. It handles API communication, error handling, and initial data structuring. Downstream assets should not need to know about the API details. """ cities = ["London", "Paris", "Berlin", "Madrid", "Rome"] records = []

for city in cities: # Using Open-Meteo free API as example response = requests.get( "https://api.open-meteo.com/v1/forecast", params={ "latitude": 51.5, # Simplified for example "longitude": -0.1, "current": "temperature_2m,wind_speed_10m" } ) data = response.json() records.append({ "city": city, "temperature_c": data["current"]["temperature_2m"], "wind_speed_kmh": data["current"]["wind_speed_10m"], "fetched_at": datetime.now() })

return pd.DataFrame(records)The ingestion asset handles all interaction with the external system. Notice how the group_name parameter organizes related assets together in the UI, while kinds adds visual badges that help identify asset types at a glance. These organizational features become essential as your asset graph grows.

import dagster as dgimport pandas as pd

@dg.asset( group_name="analytics", kinds={"python", "pandas"})def normalized_weather(raw_weather_data: pd.DataFrame) -> pd.DataFrame: """Cleans and normalizes weather data with consistent units.

Adds derived columns for different unit systems and extracts date components for time-based analysis. This standardization layer ensures downstream assets receive consistent data regardless of upstream API changes. """ df = raw_weather_data.copy() df["temperature_f"] = df["temperature_c"] * 9/5 + 32 df["wind_speed_mph"] = df["wind_speed_kmh"] * 0.621371 df["fetched_date"] = pd.to_datetime(df["fetched_at"]).dt.date return df

@dg.asset( group_name="analytics", kinds={"python", "pandas"})def weather_summary_stats(normalized_weather: pd.DataFrame) -> pd.DataFrame: """Statistical summary of weather conditions across all cities.

Provides aggregate metrics useful for dashboards and alerting. The summary includes central tendency and dispersion measures to capture both typical conditions and variability. """ return normalized_weather.agg({ "temperature_c": ["mean", "min", "max", "std"], "wind_speed_kmh": ["mean", "min", "max", "std"] }).round(2)Each analytics asset builds on the previous one, creating a clear transformation lineage. The type annotations (pd.DataFrame) serve double duty: they document the expected data format and enable Dagster to perform runtime type checking when configured.

Launch the Dagster development server to interact with your pipeline:

dagster dev -m my_pipeline.definitionsThe UI at http://localhost:3000 displays your asset graph with three nodes: raw_weather_data feeds into normalized_weather, which feeds into weather_summary_stats. Clicking any asset reveals its documentation, recent materializations, and upstream dependencies. The graph visualization makes implicit relationships explicit—something that would require extensive documentation in a task-based system.

Materializing the full pipeline is a single click on weather_summary_stats with the “Materialize all” option selected. Dagster executes raw_weather_data first, passes its DataFrame output to normalized_weather, and finally computes weather_summary_stats. Each step’s logs and outputs are captured and viewable in the UI. If any step fails, you can see exactly which asset failed, what error occurred, and what data was available from upstream assets at the time.

Note: The

kindsparameter adds visual badges in the UI, making it easier to identify asset types at a glance in large graphs. Consider establishing team conventions for kinds like “python”, “sql”, “dbt”, “api”, “ml” to create consistent visual language across your pipeline.

Resources and Configuration: Keeping Secrets Out of Your Assets

Hardcoding database connections, API keys, and file paths into asset definitions creates testing friction and deployment complexity. Resources provide Dagster’s solution: dependency injection for external systems. This pattern separates the “what” (asset logic) from the “where” (external system details), enabling the same asset code to run against different environments without modification.

A resource is a Python class that encapsulates access to an external system. Assets declare which resources they need, and Dagster provides them at runtime. This inversion of control means your assets never instantiate their own dependencies—they receive fully configured resources ready to use:

import dagster as dgfrom sqlalchemy import create_enginefrom sqlalchemy.engine import Engine

class DatabaseResource(dg.ConfigurableResource): """Resource for database connections using SQLAlchemy.

Configuration is provided at deployment time, allowing the same asset code to target different databases in different environments. """ connection_string: str

def get_engine(self) -> Engine: return create_engine(self.connection_string)

class APIClientResource(dg.ConfigurableResource): """Generic HTTP API client with authentication.

Centralizes authentication handling so individual assets don't need to manage credentials or construct authorization headers. """ base_url: str api_key: str

def fetch(self, endpoint: str) -> dict: import requests response = requests.get( f"{self.base_url}/{endpoint}", headers={"Authorization": f"Bearer {self.api_key}"} ) response.raise_for_status() return response.json()Assets receive resources through their function signature, just like upstream asset dependencies. Dagster resolves both data dependencies (other assets) and infrastructure dependencies (resources) uniformly:

import dagster as dgimport pandas as pdfrom my_pipeline.resources import DatabaseResource

@dg.assetdef sales_transactions(database: DatabaseResource) -> pd.DataFrame: """Load sales transactions from the data warehouse.

Uses the injected database resource, which may point to different databases in development, staging, and production environments. """ engine = database.get_engine() return pd.read_sql("SELECT * FROM sales.transactions", engine)Environment-specific configuration lives in the Definitions object. Production, staging, and development environments use different resource instances. This separation means you never need conditional logic inside your assets—the same code runs everywhere, only the injected resources differ:

import osimport dagster as dgfrom my_pipeline.resources import DatabaseResource, APIClientResourcefrom my_pipeline.assets import ingestion, analytics

environment = os.getenv("DAGSTER_ENV", "development")

resources = { "development": { "database": DatabaseResource( connection_string="postgresql://localhost:5432/dev_db" ), "api_client": APIClientResource( base_url="https://api.staging.example.com", api_key=os.getenv("DEV_API_KEY", "dev-key") ) }, "production": { "database": DatabaseResource( connection_string=os.getenv("PROD_DATABASE_URL") ), "api_client": APIClientResource( base_url="https://api.example.com", api_key=os.getenv("PROD_API_KEY") ) }}

defs = dg.Definitions( assets=dg.load_assets_from_modules([ingestion, analytics]), resources=resources[environment])Testing assets becomes straightforward with mock resources. Because assets receive their dependencies through injection, you can substitute test doubles without any special framework or monkey-patching. The test setup is clean and explicit:

import pandas as pdfrom my_pipeline.assets.database_assets import sales_transactions

class MockDatabaseResource: """Test double that provides in-memory SQLite instead of production database."""

def get_engine(self): # Return a SQLite in-memory engine with test data from sqlalchemy import create_engine engine = create_engine("sqlite:///:memory:") test_data = pd.DataFrame({ "id": [1, 2, 3], "amount": [100.0, 250.0, 75.0] }) test_data.to_sql("transactions", engine, index=False) return engine

def test_sales_transactions(): """Verify sales_transactions correctly loads and returns data.""" result = sales_transactions(database=MockDatabaseResource()) assert len(result) == 3 assert result["amount"].sum() == 425.0This testing pattern scales elegantly. Complex assets with multiple resource dependencies simply receive multiple mock objects. Each test can configure its mocks to produce specific scenarios—empty results, error conditions, edge cases—without affecting other tests or requiring complex fixture management.

Warning: Never commit secrets to version control. Use environment variables or a secrets manager for all credentials, even in development. Dagster integrates with secrets managers like AWS Secrets Manager and HashiCorp Vault through custom resource implementations.

Partitioned Assets: Processing Data in Manageable Chunks

Real-world datasets grow continuously. Reprocessing an entire table every time defeats the purpose of automation and wastes compute resources. Partitioned assets allow you to process data in logical chunks—typically by time—and only recompute what has changed. This incremental processing pattern is essential for any pipeline handling significant data volumes.

Time-based partitions are the most common pattern. Define a partition scheme and apply it to assets. Each partition represents a discrete unit of work that can be materialized independently:

import dagster as dgimport pandas as pdfrom datetime import datetime

daily_partitions = dg.DailyPartitionsDefinition( start_date="2026-01-01", timezone="UTC")

@dg.asset( partitions_def=daily_partitions, kinds={"python", "pandas"})def daily_events(context: dg.AssetExecutionContext) -> pd.DataFrame: """Events ingested for a specific day.

Each partition contains exactly one day's events. The partition key is available from the context, allowing the query to filter appropriately. This pattern enables efficient incremental processing where only new days need computation. """ partition_date = context.partition_key

# In practice, query only this day's data context.log.info(f"Processing events for {partition_date}")

return pd.DataFrame({ "event_id": range(100), "event_date": partition_date, "user_id": [i % 10 for i in range(100)] })

@dg.asset( partitions_def=daily_partitions, kinds={"python", "pandas"})def daily_user_activity( context: dg.AssetExecutionContext, daily_events: pd.DataFrame) -> pd.DataFrame: """Aggregated user activity metrics for a specific day.

Automatically receives the matching partition from daily_events. Dagster ensures partition alignment—the February 3rd partition of this asset receives data from the February 3rd partition upstream. """ partition_date = context.partition_key

return daily_events.groupby("user_id").agg( event_count=("event_id", "count") ).reset_index().assign(activity_date=partition_date)Partition alignment happens automatically. When you materialize a specific partition of daily_user_activity, Dagster provides that same partition’s data from daily_events. This automatic alignment eliminates an entire category of bugs where downstream processing accidentally consumes the wrong time range.

When assets have different partition granularities—for example, daily source data feeding into weekly aggregations—partition mappings define the relationship. These mappings tell Dagster how to satisfy dependencies across granularity boundaries:

import dagster as dgimport pandas as pd

daily_partitions = dg.DailyPartitionsDefinition(start_date="2026-01-01")weekly_partitions = dg.WeeklyPartitionsDefinition(start_date="2026-01-01")

@dg.asset(partitions_def=daily_partitions)def daily_sales() -> pd.DataFrame: """Sales records for a single day.""" return pd.DataFrame({"amount": [100, 200, 150]})

@dg.asset( partitions_def=weekly_partitions, ins={ "daily_sales": dg.AssetIn( partition_mapping=dg.TimeWindowPartitionMapping() ) })def weekly_sales_summary(daily_sales: pd.DataFrame) -> pd.DataFrame: """Aggregated weekly sales from daily records.

The TimeWindowPartitionMapping automatically collects all daily partitions that fall within the week being materialized. Dagster concatenates these into a single DataFrame before invoking this asset. """ return pd.DataFrame({ "total_sales": [daily_sales["amount"].sum()], "transaction_count": [len(daily_sales)] })The partition mapping handles the complexity of collecting seven daily partitions into one weekly aggregation. You declare the relationship, and Dagster manages the mechanics.

Backfilling historical data is a native operation. The Dagster UI provides a backfill interface where you select a date range, and Dagster materializes each partition in that range. You can monitor progress, pause backfills, and retry failed partitions individually. This granular control is invaluable when processing years of historical data—a single failed day doesn’t require restarting the entire backfill.

The asset graph displays partition health at a glance. Each partitioned asset shows a timeline view indicating which partitions are materialized, which are stale (upstream changed), and which have never been computed. This visibility eliminates the guesswork around data freshness that plagues task-based systems. When someone asks “is our data current?” you can answer definitively by looking at the partition status.

Pro Tip: Choose partition granularity based on your smallest unit of reprocessing, not your reporting frequency. If you might need to reprocess individual days, use daily partitions even if your reports are monthly. You can always aggregate smaller partitions into larger time windows.

Declarative Automation: Schedules, Sensors, and Auto-Materialization

Manual materialization works for development and ad-hoc analysis, but production pipelines need automation. Dagster provides three complementary mechanisms: schedules for time-based execution, sensors for event-driven execution, and auto-materialization for reactive pipelines. Understanding when to use each mechanism is key to building robust automated workflows.

Cron-based schedules trigger materialization at fixed intervals. They’re the simplest automation mechanism and work well for pipelines with predictable timing requirements:

import dagster as dgfrom my_pipeline.assets.partitioned import daily_events, daily_user_activity

daily_job = dg.define_asset_job( name="daily_pipeline", selection=[daily_events, daily_user_activity])

daily_schedule = dg.ScheduleDefinition( job=daily_job, cron_schedule="0 6 * * *", # 6 AM daily default_status=dg.DefaultScheduleStatus.RUNNING)The schedule executes at 6 AM every day, materializing both assets in dependency order. Dagster handles partitioned assets intelligently—by default, it materializes the partition corresponding to the schedule time, so the 6 AM run on February 9th materializes the February 9th partition.

Sensors poll for external conditions and trigger materialization when those conditions are met. They enable event-driven pipelines that respond to real-world changes rather than fixed schedules:

import dagster as dgfrom pathlib import Path

@dg.sensor( job=dg.define_asset_job("file_ingestion", selection="raw_file_data"))def new_file_sensor(context: dg.SensorEvaluationContext): """Triggers when new files appear in the landing zone.

Uses a cursor to track which files have been processed, ensuring each file triggers exactly one pipeline run. This pattern is common for file-based ingestion where data arrives at unpredictable times. """ landing_path = Path("/data/landing")

last_processed = context.cursor or "" new_files = sorted([ f.name for f in landing_path.glob("*.csv") if f.name > last_processed ])

if new_files: context.update_cursor(new_files[-1]) yield dg.RunRequest( run_key=new_files[-1], run_config={"files": new_files} )Sensors evaluate periodically (configurable, default 30 seconds) and can trigger runs based on any condition: new files, database changes, API responses, message queue depth. The cursor mechanism provides exactly-once semantics, preventing duplicate processing even if the sensor evaluates multiple times before a run completes.

Auto-materialization policies enable fully reactive pipelines where assets materialize themselves based on upstream freshness. This declarative approach specifies desired freshness rather than explicit schedules:

import dagster as dgimport pandas as pd

@dg.asset( automation_condition=dg.AutomationCondition.eager())def source_data() -> pd.DataFrame: """Eagerly materializes whenever possible.

The eager policy means this asset will rematerialize whenever its code changes or when explicitly requested. It serves as the stable foundation for downstream reactive assets. """ return pd.DataFrame({"value": [1, 2, 3]})

@dg.asset( automation_condition=dg.AutomationCondition.on_cron("0 * * * *"))def hourly_aggregation(source_data: pd.DataFrame) -> pd.DataFrame: """Materializes hourly, but only if source_data has changed.

Combines time-based scheduling with change detection. The asset will materialize at the top of each hour, but only if source_data has been updated since the last materialization. """ return pd.DataFrame({ "total_value": [source_data["value"].sum()], "computed_at": [pd.Timestamp.now()] })Choosing the right automation strategy depends on your use case. Schedules work well for pipelines that must run at specific times regardless of data changes—regulatory reports due at market close, daily batch jobs that downstream systems expect at fixed times. Sensors excel when external events drive your pipeline—new files arriving, webhook notifications, upstream system completions. Auto-materialization suits reactive analytics where freshness requirements vary across assets and you want the system to optimize computation automatically.

Pro Tip: Start with schedules for predictability, then introduce sensors for event-driven components. Auto-materialization is powerful but requires careful freshness policy design to avoid runaway computation or stale data. Monitor auto-materialized pipelines closely during the first few weeks.

Migration Strategy: Running Dagster Alongside Airflow

Replacing Airflow entirely is rarely practical for organizations with years of accumulated DAGs. A successful migration proceeds incrementally, demonstrating value with each phase while maintaining production stability. The goal is evolution, not revolution—each step should reduce risk and build confidence.

The first phase establishes Dagster alongside Airflow. Both systems run in production, handling different workloads. Dagster manages new pipelines while Airflow continues operating existing DAGs. This parallel operation lets your team learn Dagster patterns without the pressure of migrating critical workflows. Crucially, failures in Dagster don’t affect Airflow operations, and vice versa.

Dagster’s Airflow integration bridges the two systems during the transition period. You can wrap existing Airflow DAGs as external assets in Dagster, creating visibility into their outputs within the Dagster asset graph. Downstream Dagster assets can depend on these external assets, triggering after Airflow DAGs complete:

import dagster as dg

# Represent Airflow DAG output as external assetairflow_customer_extract = dg.AssetSpec( key="customer_data", group_name="airflow_managed", description="Customer data extracted by legacy Airflow DAG")

@dg.asset(deps=[airflow_customer_extract])def customer_segments(context: dg.AssetExecutionContext): """New segmentation logic built in Dagster.

Depends on customer_data produced by Airflow. Dagster waits for the external asset to be marked fresh before materializing this downstream asset. """ # Read data produced by Airflow DAG # Apply new segmentation logic passThis hybrid approach lets you build new transformation logic in Dagster while preserving battle-tested Airflow ingestion. Over time, you can migrate the ingestion assets as well, but the dependency relationship remains stable throughout.

Identifying high-value migration candidates accelerates the business case. Look for Airflow DAGs that suffer most from the problems described earlier: frequent debugging sessions, complex cross-DAG dependencies, painful testing cycles, or unclear data lineage. These workflows benefit most from Dagster’s asset model and provide the strongest evidence for continued migration. Start with a workflow that’s painful but not business-critical—you want room to learn without production pressure.

Common gotchas emerge when mapping Airflow operators to Dagster assets. XCom-heavy DAGs require rethinking, since Dagster assets pass data through materialized storage rather than metadata. If your Airflow tasks communicate via XCom extensively, consider whether that intermediate data should become an explicit asset. Airflow’s imperative branching (BranchPythonOperator) becomes declarative in Dagster through conditional asset dependencies or asset checks. Connections defined in Airflow’s UI become resources in Dagster code, requiring secrets management changes—but this change brings testability benefits.

Avoid the temptation to replicate Airflow patterns in Dagster. Translating a task-by-task copy of your DAG into Dagster assets misses the paradigm shift. Instead, redesign around the data products you actually care about. Many intermediate tasks in Airflow exist only to satisfy execution ordering; these often become unnecessary when you think asset-first. Take the migration as an opportunity to simplify, not just translate.

Plan for a migration timeline measured in quarters, not weeks. Each phase should deliver standalone value: better observability, easier testing, clearer documentation. Teams that rush migration often recreate their Airflow problems in Dagster syntax rather than solving them. Measure success by how much easier debugging and development become, not by how many DAGs you’ve migrated.

Key Takeaways

- Start new pipelines with Dagster’s asset-centric model—define what data you want to produce, not how to execute tasks. This mental shift is the foundation of everything else.

- Use resources for all external dependencies to enable environment switching and testability from day one. Never hardcode connection strings or credentials in asset definitions.

- Implement partitioned assets for any dataset that grows over time to avoid reprocessing historical data. Choose partition granularity based on your smallest unit of reprocessing.

- Leverage the asset graph for debugging—when metrics look wrong, trace upstream through explicit dependencies rather than reconstructing data flow mentally.

- Migrate from Airflow incrementally by wrapping existing DAGs as external assets and building new downstream assets in Dagster. Each phase should deliver standalone value while maintaining production stability.