Detecting Container Escapes with Falco: A Practical Guide to Kubernetes Runtime Security

Your container just spawned a shell and mounted the host filesystem. By the time your vulnerability scanner runs its nightly check, the attacker has already pivoted to three other nodes. They’ve read your service account tokens, queried the Kubernetes API, and established persistence across your cluster. Your image scanning pipeline? It passed with flying colors yesterday. Your network policies? Still intact—the attacker is moving through connections you explicitly allowed.

This is the gap that keeps platform engineers up at night. We’ve invested heavily in shift-left security: scanning images in CI, enforcing admission policies, running CIS benchmarks against our clusters. These controls matter. But they operate on assumptions about what will happen, not observations of what is happening. A clean image scan tells you nothing about an attacker exploiting a zero-day in your application code. A restrictive NetworkPolicy can’t distinguish between your service making legitimate API calls and a compromised pod exfiltrating secrets through the same endpoint.

Runtime security closes this gap by watching what containers actually do—at the syscall level, in real time. When a process calls setns to enter a different namespace, when something writes to /etc/shadow, when a container binary suddenly opens a raw socket—these are the signals that static analysis will never catch. Falco, the CNCF’s runtime security project, intercepts these syscalls directly from the kernel and evaluates them against detection rules in microseconds.

The question isn’t whether you need runtime visibility. It’s why traditional security controls, despite their importance, leave you blind to the attacks that matter most.

Why Static Security Fails at Runtime

Container security strategies have matured significantly, with most organizations now running vulnerability scanners against their images and enforcing network policies across their clusters. These controls are necessary—but they operate on assumptions about what will happen, not what is happening. The moment a container starts executing, a gap opens between your security posture and your actual risk exposure.

The Limits of Image Scanning

Image scanning identifies known CVEs in your container layers before deployment. It catches outdated packages, vulnerable libraries, and misconfigurations in your Dockerfiles. What it cannot do is detect exploitation. A zero-day attack against a package your scanner considers safe will execute without triggering any alert. An attacker using legitimate binaries already present in your image—living off the land—bypasses scanning entirely. The vulnerability database represents yesterday’s threats; attackers operate in real time.

Network Policies: Necessary but Insufficient

Network policies define which pods can communicate and over which ports. They segment your cluster and limit blast radius. But once traffic is allowed, network policies provide no visibility into what happens within that connection. A compromised pod communicating with an authorized service over an approved port looks identical to legitimate traffic. Exfiltration, command-and-control callbacks, and lateral movement routinely occur over connections that policy explicitly permits.

The Shift-Left Blind Spot

Shift-left security—embedding security checks earlier in development—has become standard practice. Static analysis, dependency scanning, and infrastructure-as-code validation catch problems before they reach production. This approach works well for preventable issues but assumes that prevention is complete. It is not. Attackers exploit logic flaws that no scanner detects. They leverage misconfigurations that passed policy checks. They wait until runtime to reveal their presence because that is when actual access to data and systems becomes possible.

Syscall Monitoring: Seeing What Actually Happens

Every meaningful action inside a container—reading files, spawning processes, opening network connections—requires a system call to the Linux kernel. Syscall monitoring observes these kernel interactions in real time, providing visibility into actual container behavior rather than intended behavior. When a container suddenly spawns a shell, mounts a host path, or opens a connection to an unexpected IP address, syscall monitoring sees it happen. This is detection at the point of execution, not at the point of deployment.

Static security controls remain essential for reducing attack surface. Runtime security addresses a fundamentally different question: what is happening right now, and does it match expected behavior? Falco answers this question by intercepting syscalls at the kernel level and evaluating them against security rules in real time.

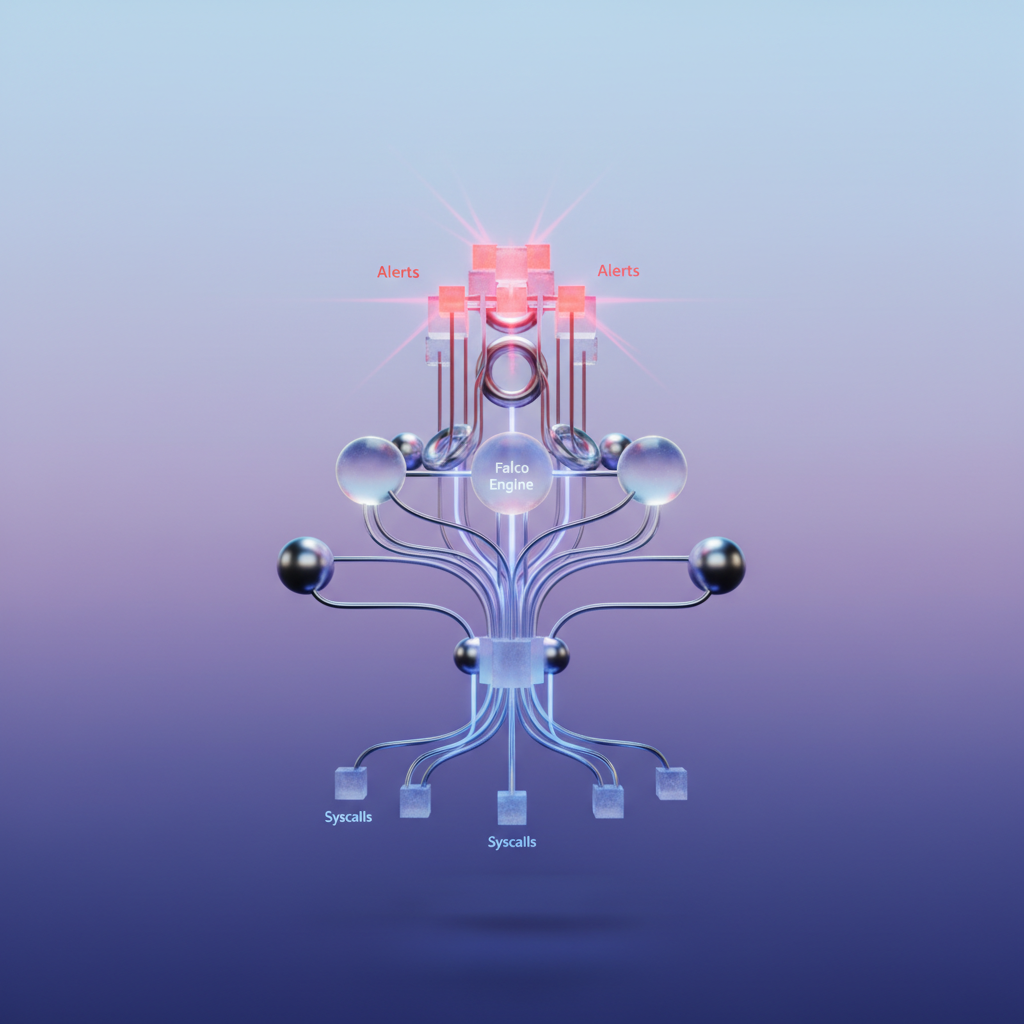

Falco Architecture: From Syscalls to Alerts

Understanding Falco’s internal architecture transforms you from a user running commands into an operator who can troubleshoot issues, tune performance, and write effective rules. At its core, Falco is an event stream processor that sits between your kernel and your alerting infrastructure.

Syscall Interception: The Foundation

Every container action—spawning a process, opening a file, establishing a network connection—translates to system calls. Falco intercepts these syscalls at the kernel level through one of two mechanisms:

eBPF probes (the modern default) attach small programs to kernel tracepoints without modifying the kernel itself. This approach offers safer deployment, easier upgrades, and better compatibility with managed Kubernetes services. The eBPF programs capture syscall arguments and return values, packaging them into events for userspace processing.

Kernel modules (the legacy driver) provide deeper instrumentation and marginally lower overhead in some scenarios. However, they require kernel header matching and carry higher operational risk—a bug can crash your node. Most production deployments now favor eBPF unless specific compatibility requirements dictate otherwise.

Both drivers feed events into Falco’s userspace libraries (libs), which enrich raw syscall data with container metadata from the container runtime. This enrichment maps a process ID to a container ID, pod name, namespace, and Kubernetes labels—context essential for writing meaningful security rules.

The Rules Engine

Falco’s rules engine evaluates each enriched event against your rule definitions in real-time. Rules consist of three components: a condition (written in Falco’s filter syntax), an output format string, and metadata like priority and tags.

The engine uses short-circuit evaluation—once a condition fails, Falco stops processing that rule for the current event. This makes rule ordering and condition structure directly impact performance. Highly selective conditions (checking specific container images or namespaces) should appear early in your rule logic.

💡 Pro Tip: Rules are evaluated in definition order. Place your most frequently triggered rules with restrictive conditions first to minimize CPU cycles spent on events that won’t match.

Output Channels

When a rule matches, Falco formats the alert and dispatches it through configured output channels. Built-in options include stdout (useful for log aggregation), syslog, file output, gRPC, and HTTP webhooks. For production alerting, Falcosidekick acts as a fanout proxy, routing alerts to Slack, PagerDuty, AWS Security Hub, Elasticsearch, and dozens of other destinations.

Performance Reality

Falco adds measurable but manageable overhead. In typical production workloads, expect 1-3% CPU overhead on nodes with moderate syscall volume. Memory footprint stays under 512MB for most deployments. The primary tuning lever is rule selectivity—broad rules that evaluate against every syscall cost more than targeted rules scoped to specific containers or behaviors.

Syscall-heavy workloads (databases, high-throughput web servers) require more careful tuning. Dropping unneeded syscall types at the driver level and using precise rule conditions keeps overhead predictable.

With this architectural foundation in place, deploying Falco becomes straightforward. The next section walks through Helm-based installation and initial configuration.

Deploying Falco on Kubernetes with Helm

With Falco’s architecture understood, let’s deploy it to a production Kubernetes cluster. The official Helm chart provides sensible defaults while exposing the configuration options you need for enterprise deployments.

Choosing Your Driver: eBPF vs Kernel Module

Falco intercepts syscalls using one of two drivers. Your choice depends on your cluster’s constraints and security requirements:

The kernel module offers the broadest compatibility and lowest overhead but requires privileged access to load the module. Some managed Kubernetes providers restrict this capability, and loading kernel modules introduces additional security considerations that your security team may need to evaluate. The kernel module approach has been battle-tested across millions of deployments and handles edge cases gracefully.

The eBPF probe runs in userspace and works on most modern kernels (5.8+) without loading kernel modules. This makes it the preferred choice for GKE, EKS, AKS, and other managed platforms where kernel module loading is restricted or discouraged. The modern eBPF driver (modern_ebpf) leverages CO-RE (Compile Once, Run Everywhere) technology, eliminating the need to compile drivers for each kernel version. This significantly simplifies deployment and updates across heterogeneous node pools.

For most production deployments, start with eBPF. Fall back to the kernel module only if you encounter compatibility issues with older kernels or require features not yet available in the eBPF implementation.

Installing Falco with Helm

Add the Falcosecurity Helm repository and create a dedicated namespace:

helm repo add falcosecurity https://falcosecurity.github.io/chartshelm repo updatekubectl create namespace falcoCreate a values file that configures Falco for production use with eBPF and proper resource limits:

driver: kind: modern_ebpf

falco: grpc: enabled: true grpc_output: enabled: true

resources: requests: cpu: 100m memory: 512Mi limits: cpu: 1000m memory: 1024Mi

tolerations: - effect: NoSchedule operator: Exists

falcosidekick: enabled: true config: slack: webhookurl: "https://hooks.slack.com/services/T0123456/B0123456/abcdefghijklmnop" minimumpriority: "warning" webhook: address: "http://security-siem.monitoring:8080/falco"Deploy Falco with your configuration:

helm install falco falcosecurity/falco \ --namespace falco \ --values falco-values.yaml \ --version 4.8.0The tolerations configuration ensures Falco runs on every node, including those with taints for system workloads or GPU nodes. This is essential for comprehensive coverage—attackers often target specialized nodes expecting reduced monitoring.

Configuring Falcosidekick for Alert Routing

Falcosidekick acts as an alert router, forwarding Falco events to your security tooling. The configuration above demonstrates two common outputs: Slack for immediate visibility and a webhook for SIEM integration. Falcosidekick supports over 50 output destinations, from cloud-native services like AWS SNS and GCP Pub/Sub to traditional security platforms like Splunk and Elasticsearch.

💡 Pro Tip: Configure

minimumpriorityper output channel. Send critical alerts to PagerDuty, warnings to Slack, and everything to your SIEM for forensic analysis. This prevents alert fatigue while maintaining complete audit trails.

For organizations using multiple alert destinations, extend the Falcosidekick configuration:

falcosidekick: enabled: true config: slack: webhookurl: "https://hooks.slack.com/services/T0123456/B0123456/abcdefghijklmnop" minimumpriority: "warning" pagerduty: routingkey: "R0123456789ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUV" minimumpriority: "critical" elasticsearch: hostport: "https://elasticsearch.monitoring:9200" index: "falco-alerts" minimumpriority: "notice"Consider adding a dead-letter queue or backup output destination. If your primary SIEM becomes unavailable during an active incident, you need alerts flowing somewhere your team can access them.

Validating Your Deployment

Verify Falco pods are running on each node:

kubectl get pods -n falco -o wideConfirm you see one Falco pod per node in your cluster, all in Running status. If pods are stuck in CrashLoopBackOff, check the logs for driver loading issues—this often indicates kernel version incompatibility or missing kernel headers.

Generate a test event by executing a shell in a running container:

kubectl run test-pod --image=nginx --restart=Neverkubectl exec -it test-pod -- /bin/bashCheck that Falco detected the shell spawn:

kubectl logs -n falco -l app.kubernetes.io/name=falco --tail=50 | grep "shell"You should see an alert containing “Terminal shell in container” with details about the pod, namespace, and user. This rule triggers because interactive shells in production containers often indicate either an attacker gaining access or an engineer bypassing proper deployment procedures—both situations worth investigating.

For Falcosidekick validation, check its logs to confirm alerts are forwarding to your configured outputs:

kubectl logs -n falco -l app.kubernetes.io/name=falcosidekick --tail=20Look for successful POST requests to your configured endpoints. Failed deliveries appear as error logs with HTTP status codes, helping you diagnose connectivity or authentication issues with downstream systems.

With Falco deployed and alerting to your security channels, you’re ready to customize its detection rules. The default ruleset catches common threats, but your environment has unique patterns that require tailored detection logic.

Understanding and Customizing Falco Rules

Falco’s power lies in its rule engine. While the default ruleset catches common attack patterns, real-world security requires rules tailored to your specific workloads and threat model. This section breaks down rule anatomy and walks through creating custom detection logic.

Anatomy of a Falco Rule

Every Falco rule consists of three core components: a condition that triggers the rule, an output message for alerts, and a priority level indicating severity. Understanding each component is essential for writing effective detection logic.

- rule: Detect Shell in Container desc: Alert when a shell is spawned inside a container condition: > spawned_process and container and proc.name in (bash, sh, zsh, dash) output: > Shell spawned in container (user=%user.name container=%container.name shell=%proc.name parent=%proc.pname cmdline=%proc.cmdline) priority: WARNING tags: [container, shell, mitre_execution]The condition field uses Falco’s filter syntax, which operates on syscall data fields. Common fields include proc.name (process name), fd.name (file descriptor name), user.name, and container.id. Conditions evaluate to true or false for each syscall event. You can combine multiple conditions using logical operators (and, or, not) to create precise detection logic that minimizes false positives while catching genuine threats.

The output field defines the alert message, interpolating runtime values using the %field.name syntax. Include enough context for responders to investigate without querying additional systems. Well-crafted output messages reduce mean time to response by providing immediate visibility into the who, what, where, and when of security events.

Priority levels range from DEBUG to EMERGENCY, matching syslog conventions. Use WARNING for suspicious activity requiring investigation and CRITICAL or higher for active exploitation attempts. Aligning priority levels with your incident response playbooks ensures alerts route to the appropriate teams with proper urgency.

Default Rules for Common Attack Patterns

Falco ships with rules covering MITRE ATT&CK techniques out of the box. These rules represent years of community knowledge about container attack patterns and provide immediate value upon deployment. Key rules for container security include:

- Terminal shell in container - Detects interactive shell access, often the first step in post-exploitation

- Write below /etc - Catches configuration tampering that could establish persistence

- Read sensitive file untrusted - Monitors access to

/etc/shadow, credentials, and other sensitive data - Launch privileged container - Flags containers with elevated capabilities that could enable escapes

- Contact K8s API from container - Identifies potential lateral movement through the Kubernetes control plane

- Modify binary dirs - Detects attempts to plant malicious executables in system paths

Review the default rules at /etc/falco/falco_rules.yaml after deployment. Many organizations disable overly noisy rules initially, then re-enable them after tuning. Document which rules you disable and why—this creates an audit trail and reminds teams to revisit tuning decisions as environments mature.

Writing Custom Rules for Your Workloads

Custom rules address threats specific to your environment that generic rulesets cannot anticipate. Consider a financial services application where database credential files should never be accessed by web-facing pods:

- rule: Unauthorized Database Credential Access desc: Detect non-database pods accessing DB credentials condition: > open_read and container and fd.name startswith /var/secrets/db-credentials and not container.image.repository = "internal-registry.example.com/postgres-client" output: > Unauthorized read of database credentials (file=%fd.name container=%container.name image=%container.image.repository pod=%k8s.pod.name namespace=%k8s.ns.name) priority: CRITICAL tags: [custom, credentials, data_exfiltration]This rule fires when any container outside the approved postgres-client image attempts to read files in the credentials directory. The specificity of the condition—combining file path patterns with image allowlisting—demonstrates how to balance security coverage with operational noise.

When writing custom rules, start by identifying your crown jewels: the data, systems, and access patterns that would cause the most damage if compromised. Build rules around those assets first, then expand coverage based on threat intelligence and incident learnings.

Using Macros and Lists for Maintainability

As your ruleset grows, macros and lists prevent duplication and simplify updates. Lists define reusable collections of values, while macros define reusable condition fragments. This abstraction becomes critical when managing rules across multiple clusters and teams.

- list: approved_package_managers items: [apt, apt-get, yum, dnf, apk]

- list: infrastructure_namespaces items: [kube-system, istio-system, falco, monitoring]

- macro: in_infrastructure_namespace condition: k8s.ns.name in (infrastructure_namespaces)

- macro: package_manager_process condition: proc.name in (approved_package_managers)

- rule: Package Manager in Application Pod desc: Detect package installation in non-infrastructure pods condition: > spawned_process and container and package_manager_process and not in_infrastructure_namespace output: > Package manager executed in application pod (command=%proc.cmdline pod=%k8s.pod.name namespace=%k8s.ns.name) priority: WARNING tags: [supply_chain, persistence]When your infrastructure namespaces change, update the list once rather than modifying every rule. This pattern scales to hundreds of rules across multiple teams. Organizations with mature Falco deployments typically maintain a shared library of macros and lists that encode institutional knowledge about their environments.

💡 Pro Tip: Store custom rules in a separate file (e.g.,

custom_rules.yaml) and mount it via the Helm chart’scustomRulesvalue. This keeps your rules version-controlled and separate from upstream defaults during upgrades.

Test rules in a staging environment before production deployment. A single overly broad condition generates thousands of false positives that obscure real threats. Use Falco’s -dry-run flag to validate rule syntax before applying changes.

With your custom rules in place, the next section demonstrates applying these techniques to detect specific container escape attempts targeting kernel vulnerabilities and misconfigurations.

Detecting Container Escape Attempts

Container escapes represent the most severe runtime threats in Kubernetes environments. When an attacker breaks out of container isolation, they gain access to the underlying host—and potentially your entire cluster. Falco’s syscall monitoring provides the detection layer that catches these attempts as they happen, giving security teams visibility into attacks that would otherwise go unnoticed until the damage is done.

The Attack Surface

Container isolation relies on Linux namespaces, cgroups, and seccomp profiles. Attackers target the boundaries between these layers through several vectors, each requiring different detection strategies:

Privileged containers run with all Linux capabilities and direct access to host devices. A single privileged: true in a pod spec disables most container isolation, granting the container root-equivalent access to the host kernel. Attackers who compromise such containers face minimal barriers to full host takeover.

Mount exploits abuse volume mounts to access sensitive host paths like /etc or the container runtime socket. Even unprivileged containers can exploit overly permissive volume configurations to read credentials, modify system files, or communicate directly with the container runtime.

Kernel vulnerabilities such as CVE-2022-0185 allow namespace escapes through filesystem operations. These exploits leverage bugs in the kernel’s handling of namespaces or cgroups, enabling attackers to break isolation boundaries without requiring elevated container privileges.

Falco’s default ruleset includes detection for these scenarios, but production environments benefit from additional custom rules tailored to your infrastructure’s specific workload patterns and security requirements.

Detecting Host Filesystem Access

When containers access host paths outside their designated volumes, Falco triggers on the underlying syscalls. Monitoring file descriptor operations reveals both successful access attempts and blocked probes that indicate reconnaissance activity:

- rule: Container Accessing Host Sensitive Paths desc: Detect container access to sensitive host filesystem locations condition: > container and (fd.name startswith /etc/shadow or fd.name startswith /etc/passwd or fd.name startswith /root/.ssh or fd.name startswith /var/run/secrets/kubernetes.io) and not proc.name in (allowed_host_readers) output: > Container accessed sensitive host path (user=%user.name command=%proc.cmdline file=%fd.name container=%container.name image=%container.image.repository pod=%k8s.pod.name namespace=%k8s.ns.name) priority: CRITICAL tags: [container, filesystem, escape]

- list: allowed_host_readers items: [kubelet, containerd-shim]This rule catches reconnaissance attempts where attackers probe for credential files or Kubernetes service account tokens. The file paths monitored represent high-value targets that attackers consistently seek during post-exploitation phases.

Container Runtime Socket Access

Access to the Docker or containerd socket from within a container enables full host compromise. An attacker with socket access can launch privileged containers, mount the host filesystem, and escape trivially. This attack vector is particularly dangerous because it requires no kernel exploits—only network access to an exposed socket:

- rule: Container Runtime Socket Access desc: Detect attempts to access container runtime sockets condition: > container and (fd.name = /var/run/docker.sock or fd.name = /run/containerd/containerd.sock or fd.name = /var/run/crio/crio.sock) and not k8s.ns.name = kube-system output: > Runtime socket accessed from container (user=%user.name command=%proc.cmdline socket=%fd.name container=%container.name image=%container.image.repository namespace=%k8s.ns.name) priority: CRITICAL tags: [container, runtime, escape]The rule excludes kube-system namespace access since system components legitimately interact with the runtime. However, any other namespace accessing these sockets warrants immediate investigation.

💡 Pro Tip: Some CI/CD tools legitimately need Docker socket access for building images. Create explicit exceptions for these workloads using the

k8s.pod.labelfield rather than broad namespace exclusions. This maintains detection coverage while accommodating operational requirements.

Namespace Breakout Detection

Namespace manipulation indicates an active escape attempt. The setns syscall allows processes to join different namespaces—behavior that legitimate container workloads never exhibit. Detecting this syscall provides early warning of sophisticated escape techniques:

- rule: Namespace Change Attempt desc: Detect attempts to change Linux namespaces from container condition: > container and evt.type = setns and not proc.name in (runc, containerd-shim, crio) output: > Namespace change attempted in container (user=%user.name command=%proc.cmdline namespace_type=%evt.arg.ns container=%container.name image=%container.image.repository pod=%k8s.pod.name) priority: CRITICAL tags: [container, namespace, escape]

- rule: Mount Namespace Escape via Proc desc: Detect access to host namespace via /proc condition: > container and fd.name startswith /proc/1/ and not proc.name in (pause, tini) output: > Container accessed init process namespace (command=%proc.cmdline path=%fd.name container=%container.name) priority: HIGH tags: [container, namespace, escape]These rules target the specific syscalls and file accesses that precede successful container escapes. Access to /proc/1/ is particularly significant because PID 1 on the host sits outside container namespaces, making it a common pivot point for breakout attempts.

With detection rules in place, the next challenge becomes separating genuine threats from operational noise. Tuning these rules for your production environment prevents alert fatigue while maintaining security coverage.

Reducing Noise: Tuning Rules for Production

A Falco deployment generating hundreds of alerts per hour becomes background noise that teams ignore. Production-ready runtime security requires systematic tuning that maintains detection capability while eliminating false positives from legitimate workload behavior.

Identifying False Positives

Before tuning, establish a baseline by running Falco in observation mode for 24-48 hours. Common sources of false positives include:

- Package managers running during container initialization

- Health check processes spawning shells

- Debugging tools used by operators during incidents

- Sidecar containers with elevated privileges (service meshes, log collectors)

Export alerts to a queryable system and analyze patterns by rule name, container image, and process:

kubectl logs -n falco -l app.kubernetes.io/name=falco --since=24h | \ jq -r 'select(.priority == "Warning") | [.rule, .output_fields["container.image.repository"]] | @tsv' | \ sort | uniq -c | sort -rn | head -20Using Exceptions to Whitelist Known Patterns

Falco’s exception framework allows surgical tuning without modifying base rules. Exceptions define specific conditions under which a rule should not fire:

- rule: Terminal shell in container exceptions: - name: known_health_checks fields: [container.image.repository, proc.name] comps: [=, =] values: - [docker.io/library/nginx, curl] - [gcr.io/my-project/api-server, sh] - name: debugging_namespace fields: [k8s.ns.name] comps: [=] values: - [debug-allowed]For broader modifications, append rules extend or override existing definitions:

- rule: Write below root append: true condition: and not (container.image.repository = "docker.io/library/postgres" and fd.name startswith /var/lib/postgresql)💡 Pro Tip: Always use

append: trueinstead of copying entire rules. This ensures your customizations survive Falco upgrades and reduces configuration drift.

Balancing Coverage with Alert Fatigue

Prioritize tuning rules by severity and frequency. A high-severity rule firing twice daily warrants investigation, while a medium-severity rule firing every minute demands immediate tuning or temporary disabling.

Create a priority matrix for your tuning decisions:

| Alert Frequency | High Severity | Medium Severity | Low Severity |

|---|---|---|---|

| >100/hour | Tune immediately | Disable, investigate | Disable |

| 10-100/hour | Investigate | Tune this week | Disable |

| <10/hour | Investigate each | Sample review | Log only |

Iterative Tuning Workflow

Treat rule tuning as an ongoing process, not a one-time configuration:

- Deploy new rules in warning mode with reduced priority during the first week

- Collect baseline data before any tuning

- Add exceptions incrementally, documenting the business justification for each

- Review tuning decisions quarterly as workloads and threat models evolve

- Test exceptions in staging before promoting to production

- rule: Detect outbound connections to crypto mining pools desc: Staged deployment - warning only for first 7 days priority: WARNING tags: [network, cryptomining, staged] # Promote to CRITICAL after validation periodMaintaining a changelog for your custom rules ensures audit compliance and helps onboard new team members to your security posture decisions.

With tuned rules generating actionable alerts, the next step is connecting Falco to your broader security operations workflow for automated response and incident management.

Integrating Falco into Your Security Operations

Detecting threats is only half the battle. Without proper integration into your security operations workflow, Falco alerts become noise that teams eventually ignore. This section covers the essential integrations that transform Falco from a detection tool into an actionable security layer.

Routing Alerts to Your SIEM

Falco supports multiple output channels out of the box. For enterprise environments, the Falcosidekick companion tool provides over 50 integrations including Splunk, Elasticsearch, Datadog, and cloud-native options like AWS Security Hub and Google Chronicle.

Configure Falcosidekick to enrich alerts with Kubernetes metadata—namespace, pod labels, node information—before forwarding. This context proves invaluable during incident investigation. Set up severity-based routing so critical alerts (priority “Critical” or “Emergency”) reach on-call channels immediately while lower-priority events flow to your SIEM for correlation and trending analysis.

Automated Response with Event-Driven Tooling

Falco pairs naturally with Kubernetes event-driven frameworks. Tools like Falco Talon and custom Kubernetes operators can consume Falco events and execute automated responses: killing suspicious pods, cordoning compromised nodes, or triggering forensic data collection before evidence disappears.

Start conservatively with automated responses. Begin with low-risk actions like labeling suspicious pods or scaling down deployments, then graduate to more aggressive remediation as you build confidence in your rule accuracy.

💡 Pro Tip: Always implement a circuit breaker in automated response systems. A misconfigured rule triggering mass pod termination causes more damage than most attacks.

Building Actionable Runbooks

Each high-priority Falco rule should map to a documented runbook. Cover the essential questions: What does this alert mean? What evidence should responders collect? What are the immediate containment steps? Include kubectl commands for gathering pod specs, reviewing recent events, and capturing container state.

Security Posture Dashboards

Export Falco metrics to Prometheus and build Grafana dashboards tracking alert volume by rule, namespace, and severity. Monitor trends over time—a sudden spike in specific alerts often indicates either an attack in progress or a deployment change requiring rule updates.

With Falco integrated into your security operations, you have a complete runtime security solution that detects threats and enables rapid response.

Key Takeaways

- Deploy Falco using the eBPF driver with Helm and configure Falcosidekick to route alerts to your incident management system within your first week

- Start with default rules enabled, then iteratively add exceptions for known workload patterns to reduce false positives by 80% within the first month

- Write custom rules targeting your specific high-value assets—focus on detecting host filesystem access, privileged operations, and runtime shell execution in production namespaces

- Create response runbooks for your top five most critical Falco rules so your team knows exactly how to investigate and remediate each alert type