C# 14 Extension Members: Rewriting How We Compose Behavior in .NET

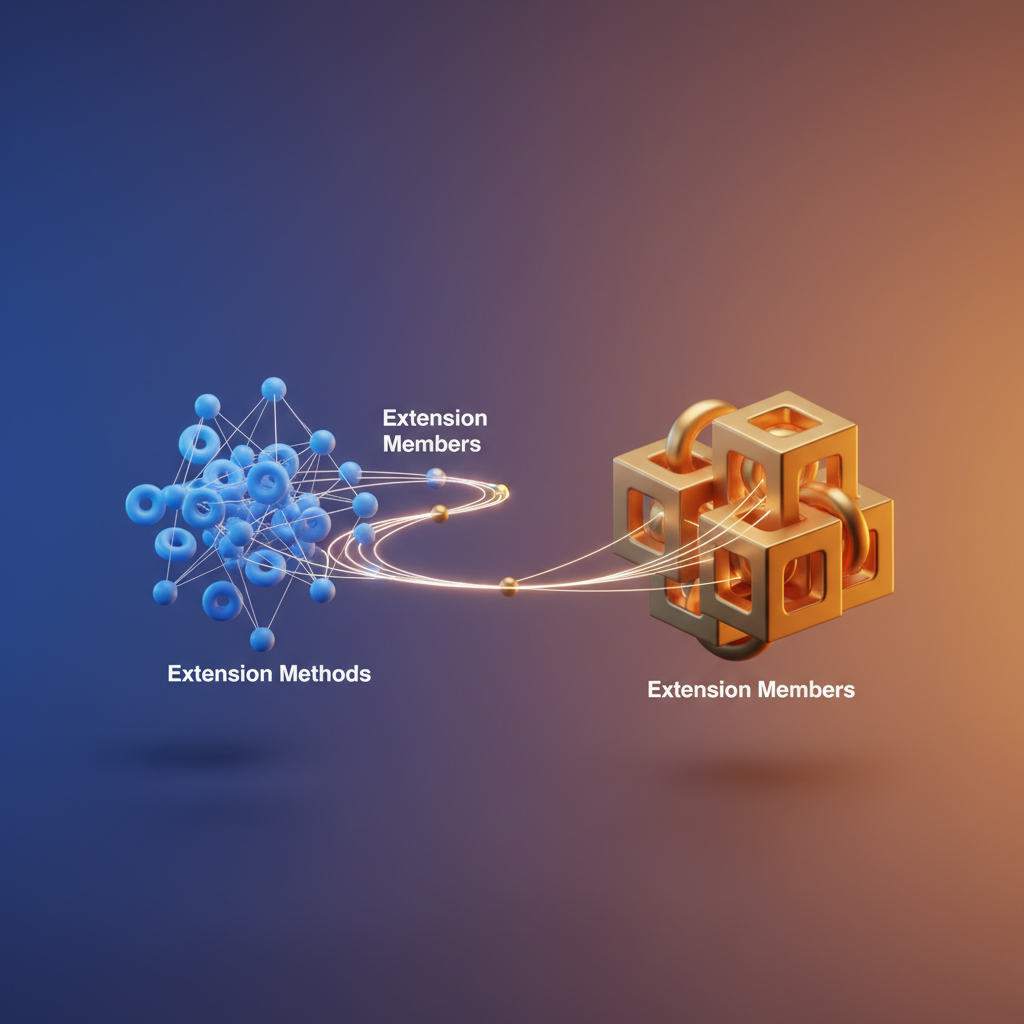

You’ve been writing extension methods for over a decade. They work, but you’ve hit their limits—no state, no properties, no way to truly extend a type’s surface area. C# 14 changes everything with extension members, and if you’re not paying attention, you’ll miss the biggest shift in .NET composition since LINQ.

Think about the last time you needed to add a computed property to a type you didn’t own. Maybe you wanted order.TotalWithTax on a third-party e-commerce model, or user.FullName on an Entity Framework entity without polluting your domain. You reached for an extension method, wrote GetTotalWithTax(), and felt that familiar friction. It works, but it’s not right. Properties communicate intent differently than methods. order.TotalWithTax reads like data. order.GetTotalWithTax() reads like computation. That distinction matters when you’re building APIs that other developers will use for years.

The workarounds we’ve developed are telling. Wrapper classes that duplicate half the original type’s surface. Static helper classes that balloon into thousand-line monstrosities. The “extension property” pattern where you stash state in a ConditionalWeakTable and pretend that’s not a code smell. We’ve normalized these hacks because extension methods gave us 80% of what we needed, and 80% felt revolutionary in 2007.

But here’s the thing about that remaining 20%—it’s where composition patterns live or die. It’s the difference between code that reads like a natural extension of the platform and code that constantly reminds you it’s bolted on from the outside.

C# 14’s extension members don’t just close this gap. They redefine what “extending a type” means in .NET. Before we dig into the new syntax and capabilities, let’s be precise about what we’ve been missing—and why those limitations shaped (and sometimes distorted) how we architect .NET applications.

The Extension Method Wall: Why 15 Years Wasn’t Enough

Extension methods arrived in C# 3.0 with LINQ, and they changed everything. Suddenly, you could add behavior to types you didn’t own. IEnumerable<T> became infinitely more powerful without Microsoft touching the interface. Third-party libraries gained fluent APIs. The .NET ecosystem embraced functional composition.

Then we hit the wall.

The Promise vs. The Reality

Extension methods solved one problem elegantly: adding methods to existing types. But software architecture demands more than methods. We need properties for computed values. We need operators for domain-specific semantics. We need indexers for collection-like access patterns. We need the ability to maintain state across operations without polluting method signatures.

Consider a common scenario—wrapping a third-party Money type with validation logic:

public static class MoneyExtensions{ // We want this to be a property, but we're forced into a method public static bool IsValid(this Money money) => money.Amount >= 0;

// We want operator overloading, but this is the best we can do public static Money Add(this Money left, Money right) { if (left.Currency != right.Currency) throw new CurrencyMismatchException(); return new Money(left.Amount + right.Amount, left.Currency); }

// We want an indexer for multi-currency wallets, impossible with extensions public static Money GetCurrency(this Wallet wallet, string currencyCode) => wallet.Balances.First(b => b.Currency == currencyCode);}Every experienced .NET developer recognizes this pattern. You want if (payment.IsValid) but you write if (payment.IsValid()). You want total = price + tax but you write total = price.Add(tax). You want wallet["USD"] but you write wallet.GetCurrency("USD"). The parentheses and method names accumulate into cognitive overhead that compounds across a codebase, making code harder to read and maintain over time.

The Workarounds That Became Technical Debt

Teams developed patterns to cope. None of them are good.

The wrapper class approach creates parallel hierarchies that drift out of sync with the original types. You end up with RichMoney wrapping Money, but every API boundary requires conversion. Implicit operators help but introduce their own subtle bugs. The partial class hack only works for types you own, leaving third-party integrations stranded. The “helper” static class becomes a dumping ground for loosely related functionality, violating cohesion principles and making discoverability a nightmare.

The ConditionalWeakTable pattern attempts to simulate properties with state by associating data with objects without preventing garbage collection. It works, but the complexity is rarely justified, and debugging becomes significantly harder when state lives in static dictionaries rather than on instances.

The most insidious workaround is accepting the limitation and designing around it:

// Instead of: order.IsValid// We build elaborate fluent chains to hide the awkwardnessvar result = order .ValidateWith(new OrderValidator()) .ThenCheck(o => o.Items.All(i => i.IsAvailable())) .ThenCheck(o => o.Customer.HasValidPaymentMethod()) .Execute();This works. It’s testable. But it’s also ceremony masking a language limitation. New team members question why simple validation requires a builder pattern, and the answer—“because C# can’t do extension properties”—never feels satisfying.

Pro Tip: If you’ve ever created a

*Extensions.csfile that grew beyond 500 lines, you’ve experienced the architectural pressure that extension methods create. The feature encourages method sprawl because it’s the only composition tool available.

The fundamental issue is that extension methods treat behavior addition as a second-class concern. You can extend, but only in the most limited way. Properties, operators, static members, and indexers remain locked behind inheritance or direct type ownership. This asymmetry forces developers to choose between clean APIs and clean architecture—a false choice that has shaped countless design decisions across the .NET ecosystem.

C# 14 finally breaks through this wall. Extension members don’t just add syntax—they reshape how we think about type composition entirely.

Extension Members Unpacked: The New Syntax and Semantics

C# 14 introduces a fundamental shift in how we declare extensions. The new implicit extension syntax replaces the static-class-with-static-methods pattern with a dedicated language construct that feels native to the type system. This isn’t merely syntactic sugar—it’s a semantic enhancement that unlocks capabilities previously impossible with traditional extension methods.

The Implicit Extension Declaration

The core syntax introduces implicit extension as a first-class declaration:

public implicit extension StringEnhancements for string{ public bool IsValidEmail => Regex.IsMatch(this, @"^[^@\s]+@[^@\s]+\.[^@\s]+$");

public string Truncate(int maxLength, string suffix = "...") => this.Length <= maxLength ? this : string.Concat(this.AsSpan(0, maxLength - suffix.Length), suffix);

public static string Empty => string.Empty;}The for clause specifies the extended type, and this refers to the instance within member bodies. No more repetitive first parameters—the receiver is implicit. This subtle change dramatically reduces boilerplate and aligns extension syntax with how we naturally think about adding members to types.

This declaration creates extension properties (IsValidEmail), extension methods (Truncate), and extension static members (Empty). All three were impossible with traditional extension methods. The declaration also supports access modifiers, enabling internal extensions for domain-specific enhancements that shouldn’t leak outside assembly boundaries.

Extension Properties and Indexers

Extension properties eliminate the awkward GetXxx() method pattern that plagued traditional extensions:

public implicit extension CollectionEnhancements<T> for ICollection<T>{ public bool IsEmpty => this.Count == 0;

public bool IsNotEmpty => this.Count > 0;

public T? FirstOrNull => this.Count > 0 ? this.First() : default;}The difference in readability is substantial. Compare collection.IsEmpty to collection.GetIsEmpty() or the even worse CollectionExtensions.IsEmpty(collection). Properties express state; methods express behavior. Now your extensions can respect this semantic distinction.

Extension indexers bring the same natural syntax to index-based access:

public implicit extension DictionaryEnhancements<TKey, TValue> for IDictionary<TKey, TValue> where TKey : notnull{ public TValue this[TKey key, TValue defaultValue] => this.TryGetValue(key, out var value) ? value : defaultValue;}

// Usagevar config = new Dictionary<string, string> { ["timeout"] = "30" };string retryCount = config["retryCount", "3"]; // Returns "3"Pro Tip: Extension indexers with additional parameters create expressive APIs for fallback values without polluting the base type’s interface.

Static Extension Members

Static members on extensions open new composition possibilities that fundamentally change how you structure library code:

public implicit extension ResultEnhancements<T> for Result<T>{ public static Result<T> Success(T value) => new(value, isSuccess: true);

public static Result<T> Failure(string error) => new(default!, isSuccess: false, error);

public static Result<T> FromException(Exception ex) => Failure(ex.Message);}

// Called as if static members existed on Result<T>var result = Result<Order>.Success(order);This pattern lets you add factory methods to types you don’t control—interfaces, third-party classes, or framework types. Consider the implications: you can now extend ILogger<T> with static factory methods, add Parse methods to types that lack them, or create domain-specific constructors for framework types. The boundary between “types you own” and “types you use” becomes porous in exactly the right way.

Compiler Resolution Rules

The compiler resolves extension members using a refined lookup algorithm that maintains backward compatibility while establishing clear precedence rules. When you write myString.IsValidEmail, the compiler:

- Searches instance members on

stringand its base types - Searches extension members in scope, starting from the innermost namespace

- Falls back to traditional extension methods

Extension members take precedence over traditional extension methods when both are in scope. This ordering matters for migration—new extension members shadow old extension methods with matching signatures. The design ensures that upgrading a library to use the new syntax doesn’t break existing consumers, but new code benefits from the enhanced semantics.

// Traditional extension methodpublic static class LegacyExtensions{ public static bool IsValid(this string s) => !string.IsNullOrEmpty(s);}

// New extension memberpublic implicit extension ModernExtensions for string{ public bool IsValid => !string.IsNullOrWhiteSpace(this);}

// ModernExtensions.IsValid wins when both are importedGeneric type inference works as expected. The compiler infers type arguments from the receiver type, just as it does with traditional extension methods:

public implicit extension EnumerableEnhancements<T> for IEnumerable<T>{ public IEnumerable<T> WhereNotNull() where T : class => this.Where(x => x is not null)!;}

// Compiler infers T from the receiverList<string?> names = ["Alice", null, "Bob"];IEnumerable<string> valid = names.WhereNotNull(); // T inferred as string?The implicit keyword indicates automatic availability—these members appear on instances without explicit casting. C# 14 also supports explicit extension for scenarios where you want opt-in behavior, requiring a cast to the extension type before members become accessible. Implicit extensions cover most practical use cases, but explicit extensions prove valuable when you need to avoid naming collisions or provide specialized behavior that shouldn’t appear in IntelliSense by default.

Understanding these resolution rules becomes critical when you start migrating existing extension methods. Let’s examine how these new capabilities reshape composition patterns in real-world architectures.

Composition Over Inheritance: Extension Members in Practice

Extension members fundamentally shift how we approach composition in .NET. Where we previously reached for inheritance hierarchies or wrapper classes, we now have a lightweight mechanism that attaches behavior directly to types we don’t own. This represents a significant evolution in how C# developers think about extending functionality—moving away from the rigid structures of classical object-oriented design toward a more flexible, functional approach. This section explores three practical patterns that demonstrate this shift and provides guidance on when each approach delivers the most value.

Adding Computed Properties to Third-Party Types

Consider working with HttpResponseMessage from System.Net.Http. You frequently need to check whether a response falls into specific status code ranges. Before C# 14, you’d write extension methods that read awkwardly:

public static class HttpResponseExtensions{ public static bool IsSuccessful(this HttpResponseMessage response) => (int)response.StatusCode >= 200 && (int)response.StatusCode < 300;}

// Usage: if (response.IsSuccessful()) { ... }The parentheses betray the implementation detail—this is a method masquerading as a property. Developers reading the code must pause to consider whether IsSuccessful() performs computation or simply returns a value, creating unnecessary cognitive friction.

With extension members, you add properties that feel native to the type:

public static class HttpResponseExtensions{ extension(HttpResponseMessage response) { public bool IsSuccessful => (int)response.StatusCode >= 200 && (int)response.StatusCode < 300; public bool IsClientError => (int)response.StatusCode >= 400 && (int)response.StatusCode < 500; public bool IsServerError => (int)response.StatusCode >= 500 && (int)response.StatusCode < 600; public int NumericStatusCode => (int)response.StatusCode; }}var response = await httpClient.GetAsync("https://api.example.com/users/42");

if (response.IsSuccessful){ var user = await response.Content.ReadFromJsonAsync<User>();}else if (response.IsClientError){ logger.LogWarning("Client error: {StatusCode}", response.NumericStatusCode);}The code reads as if these properties were always part of HttpResponseMessage. No parentheses, no method-call syntax for what is conceptually a property access. This semantic clarity compounds across a codebase—every call site becomes marginally more readable, and those margins add up to significant improvements in maintainability.

Building Fluent APIs Without Wrapper Classes

Fluent builders traditionally require dedicated wrapper classes that carry state through the chain. These wrappers introduce allocation overhead, complicate debugging (you’re always one layer removed from the actual data), and require maintenance as the underlying type evolves. Extension members enable fluent APIs that operate directly on the target type, eliminating these pain points entirely.

public static class QueryExtensions{ extension<T>(IQueryable<T> query) { public IQueryable<T> WhereDateInRange( Expression<Func<T, DateTime>> selector, DateTime? start, DateTime? end) { var result = query; if (start.HasValue) { var startFilter = Expression.Lambda<Func<T, bool>>( Expression.GreaterThanOrEqual(selector.Body, Expression.Constant(start.Value)), selector.Parameters); result = result.Where(startFilter); } if (end.HasValue) { var endFilter = Expression.Lambda<Func<T, bool>>( Expression.LessThanOrEqual(selector.Body, Expression.Constant(end.Value)), selector.Parameters); result = result.Where(endFilter); } return result; }

public IQueryable<T> Paginate(int page, int pageSize) => query.Skip((page - 1) * pageSize).Take(pageSize); }}var orders = dbContext.Orders .WhereDateInRange(o => o.CreatedAt, request.StartDate, request.EndDate) .Where(o => o.Status == OrderStatus.Completed) .Paginate(request.Page, request.PageSize) .ToListAsync();This approach eliminates the need for QueryBuilder<T> wrapper classes while maintaining the fluent chaining pattern that makes query construction readable. The debugger shows the actual IQueryable<T> at each step, and you can freely intermix your extension members with LINQ’s built-in methods without adapter gymnastics.

When Extension Members Beat the Decorator Pattern

The decorator pattern adds behavior by wrapping objects. It requires interface definitions, wrapper class implementations, and careful constructor delegation. While powerful for intercepting method calls or maintaining separate state, decorators introduce significant ceremony for simpler use cases. Extension members offer a lighter alternative when you need to add behavior without modifying state.

public static class LoggingExtensions{ extension(ILogger logger) { public IDisposable BeginOperationScope(string operationName, string correlationId) { return logger.BeginScope(new Dictionary<string, object> { ["OperationName"] = operationName, ["CorrelationId"] = correlationId, ["StartedAt"] = DateTime.UtcNow }); }

public void LogOperationResult(string operation, bool success, TimeSpan duration) { if (success) logger.LogInformation("Operation {Operation} completed in {Duration}ms", operation, duration.TotalMilliseconds); else logger.LogWarning("Operation {Operation} failed after {Duration}ms", operation, duration.TotalMilliseconds); } }}A decorator-based approach would require ILogger wrapper implementations for each logging provider, or a generic wrapper that delegates all interface members to an inner instance. That’s dozens of lines of boilerplate for functionality that extension members express in a few lines. More importantly, decorators must be explicitly instantiated and injected—extension members are available wherever the namespace is imported.

Pro Tip: Extension members shine for stateless behavior additions. When you need to maintain state across calls or intercept/modify the underlying type’s behavior, the decorator pattern remains the appropriate choice. A simple heuristic: if you’d need a field in your decorator, you need a decorator. If you’re just computing values from existing state, reach for extension members.

The pattern holds: if you’re adding computed values or convenience methods that derive from existing state, extension members provide cleaner composition. If you’re wrapping behavior to intercept calls or maintain separate state, stick with traditional patterns. This isn’t an either-or decision—many real-world systems combine both approaches, using extension members for ergonomic conveniences and decorators for cross-cutting concerns like caching or authorization.

These composition patterns become even more powerful when combined with C# 14’s improved null-safety features. The next section examines how the field keyword and defensive patterns work alongside extension members to build robust APIs.

The Null-Safety Story: Field Keyword and Defensive Patterns

C# 14 delivers two features that, when combined with extension members, create a powerful toolkit for building APIs that handle edge cases gracefully. The field keyword eliminates backing field boilerplate, while extension properties give you new places to inject null-safety logic. Together, they enable defensive patterns that were previously awkward or impossible to express cleanly.

The Field Keyword: Eliminating Ceremony

Before C# 14, adding validation or transformation to an auto-property required expanding it into a full property with an explicit backing field:

private string _userName = string.Empty;

public string UserName{ get => _userName; set => _userName = value?.Trim() ?? throw new ArgumentNullException(nameof(value));}The field keyword lets you keep the concise auto-property syntax while adding custom logic:

public string UserName{ get => field; set => field = value?.Trim() ?? throw new ArgumentNullException(nameof(value));}The compiler generates the backing field automatically. You reference it with field in your accessors. This removes the naming ceremony and keeps the property self-contained.

This pattern proves particularly valuable for enforcing invariants. Consider a property that must always contain a normalized value:

public string Email{ get => field; set => field = value?.ToLowerInvariant().Trim() ?? throw new ArgumentNullException(nameof(value));}Every assignment flows through your setter logic, guaranteeing the stored value meets your requirements. The field keyword makes this level of control accessible without the traditional ceremony of declaring and naming backing fields manually.

Extension Properties with Null-Conditional Chains

Extension properties shine when you need to expose computed values that navigate potentially null object graphs. Consider a domain where you frequently access nested configuration:

public static class ConfigurationExtensions{ public static string? EffectiveConnectionString(this ApplicationConfig config) { return config?.Database?.ConnectionStrings?.Primary ?? config?.Database?.ConnectionStrings?.Fallback ?? config?.GlobalDefaults?.DefaultConnectionString; }}With C# 14 extension members, this becomes a true property on the type:

public extension ConfigurationExtension for ApplicationConfig{ public string? EffectiveConnectionString => Database?.ConnectionStrings?.Primary ?? Database?.ConnectionStrings?.Fallback ?? GlobalDefaults?.DefaultConnectionString;}The calling code reads naturally: config.EffectiveConnectionString. No method parentheses, no utility class to remember. The null-conditional logic stays encapsulated where it belongs.

This approach scales well across your codebase. When multiple developers work with the same deeply nested structures, centralizing the null-navigation logic in extension properties prevents inconsistent handling. One team member might forget the fallback check; the extension property ensures everyone gets the same defensive behavior automatically.

Building Defensive APIs

Combining these features lets you create APIs that fail gracefully without scattering null checks throughout your codebase. Here’s a pattern for wrapping third-party types with defensive extensions:

public extension HttpResponseExtension for HttpResponseMessage{ public bool IsSuccessful => IsSuccessStatusCode && Content is not null;

public string SafeReasonPhrase => ReasonPhrase ?? StatusCode.ToString();

public async Task<T?> DeserializeOrDefaultAsync<T>() where T : class { if (!IsSuccessful) return default;

try { var content = await Content.ReadAsStringAsync(); return string.IsNullOrWhiteSpace(content) ? default : JsonSerializer.Deserialize<T>(content); } catch (JsonException) { return default; } }}Consuming code becomes declarative:

var response = await httpClient.GetAsync("https://api.example.com/users/42");var user = await response.DeserializeOrDefaultAsync<User>();

if (user is null){ logger.LogWarning("Failed to retrieve user: {Reason}", response.SafeReasonPhrase);}Notice how the extension consolidates multiple failure modes—HTTP errors, null content, empty responses, and malformed JSON—into a single predictable outcome. Callers don’t need to understand every edge case; they simply check for null and proceed accordingly.

Pro Tip: Extension members make the “Parse vs. TryParse” pattern trivial to add to any type. Create a

TryGetextension method alongside properties that throw, giving consumers control over failure handling.

The field keyword reduces friction when you need stateful properties with validation. Extension members let you attach these defensive patterns to types you don’t control. The combination produces APIs that guide developers toward safe usage without requiring them to understand every edge case. Your team writes less defensive boilerplate, and the patterns remain consistent across the entire codebase.

With these patterns established, the question becomes practical: how do you migrate an existing codebase from extension methods to extension members without breaking consumers?

Migration Strategy: From Extension Methods to Extension Members

Adopting extension members in an existing codebase requires a measured approach. The feature introduces powerful new capabilities, but rushing migration creates unnecessary risk. Here’s how to systematically identify opportunities and execute the transition.

Identifying Migration Candidates

Not every extension method deserves promotion to an extension member. Start by auditing your codebase for these high-value patterns:

Stateful extension scenarios represent the strongest candidates. Any extension method that relies on ConditionalWeakTable, external dictionaries, or repeated calculations to simulate state belongs at the top of your migration list. Extension members with backing fields eliminate these workarounds entirely.

Interface enhancement clusters come next. When you have five or more extension methods targeting the same interface—particularly when they share common logic or could benefit from property semantics—consolidating them into an extension block improves discoverability and maintainability.

Property-like behavior signals a natural fit. Extension methods named GetX() and SetX() that operate on the same conceptual value convert cleanly to extension properties, making the API more intuitive for consumers.

Pro Tip: Run a quick grep for

this IEnumerable,this ICollection, and your core domain interfaces. These clusters often reveal the highest-impact migration targets.

Backward Compatibility Considerations

C# 14 extension members coexist with traditional extension methods. The compiler resolves calls using existing precedence rules: instance members take priority, followed by extension members in the nearest enclosing namespace. This means your existing extension methods continue functioning without modification.

However, naming collisions require attention. If you introduce an extension property Count on a type that already has an extension method Count(), calling code behaves differently depending on syntax. Method invocation syntax continues calling the extension method; property access syntax invokes the new extension property. Document these distinctions explicitly during migration to prevent confusion.

Gradual Adoption Path

Phase your migration across three stages. First, introduce extension members for new functionality only—establish patterns and team familiarity without touching stable code. Second, migrate high-value candidates identified in your audit, prioritizing stateful scenarios where the improvement is most dramatic. Third, consolidate remaining extension method clusters into cohesive extension blocks during natural refactoring opportunities.

Mark legacy extension methods with [Obsolete] attributes pointing to their extension member replacements. This guides consumers toward the new API while maintaining full backward compatibility throughout the transition period.

With migration strategy established, understanding what happens at compile time becomes essential—particularly for performance-sensitive applications where the abstraction cost matters.

Performance and Compilation: What Actually Happens Under the Hood

One question surfaces immediately when evaluating any new language feature: what’s the runtime cost? For extension members, the answer is reassuring. The C# compiler and JIT work together to ensure extension members perform identically to traditional approaches in nearly all scenarios.

IL Generation: Same Patterns, Same Performance

Extension members compile down to the same IL patterns you already trust. The compiler transforms extension member syntax into static method calls with the extended type as the first parameter—exactly like classic extension methods.

// Extension method (C# 3.0+)public static class StringExtensions{ public static bool IsValidEmail(this string value) => value.Contains('@') && value.Contains('.');}

// Extension member (C# 14)public extension StringValidation for string{ public bool IsValidEmail => this.Contains('@') && this.Contains('.');}Both approaches generate virtually identical IL:

.method public hidebysig static bool IsValidEmail(string value) cil managed{ ldarg.0 ldstr "@" call bool [System.Runtime]System.String::Contains(string) brfalse.s IL_0018 ldarg.0 ldstr "." call bool [System.Runtime]System.String::Contains(string) ret}The this reference in extension members becomes the first argument, just as it does with extension methods. No virtual dispatch, no heap allocations, no hidden costs.

JIT Inlining: The Real Performance Story

The JIT compiler treats extension member calls as standard static method invocations, making them prime candidates for inlining. When the JIT determines a method is small enough and called frequently, it eliminates the call overhead entirely by embedding the method body at the call site.

public extension NumericOps for int{ public bool IsEven => (this & 1) == 0; public int Squared => this * this;}

// Hot path in your applicationpublic int ProcessValues(int[] data){ int sum = 0; foreach (var n in data) { if (n.IsEven) sum += n.Squared; } return sum;}The JIT inlines both IsEven and Squared directly into the loop body. The resulting machine code contains no method calls—just the bitwise AND and multiplication instructions. Benchmark this against hand-inlined code and you’ll measure identical throughput.

Zero-Overhead Scenarios

Extension members achieve zero overhead when:

- The method body is small (under ~32 bytes of IL for Tier 1 JIT)

- No virtual dispatch is involved (extension members are always static)

- The extended type is a value type or sealed class (no polymorphic considerations)

For extension properties backed by the field keyword, the generated IL includes a static field access. This adds a single memory read—the same cost as any static field in your codebase.

Pro Tip: Use

[MethodImpl(MethodImplOptions.AggressiveInlining)]on extension member methods if profiling shows the JIT isn’t inlining a performance-critical path. This hint applies to extension members just as it does to regular methods.

When to Profile, Not Assume

Extension members carrying complex logic or capturing closures behave like any other method with those characteristics. The extension syntax doesn’t add overhead, but it also doesn’t eliminate costs inherent to what the method actually does. If your extension member allocates, boxes value types, or performs I/O, those costs remain.

The compilation model for extension members slots cleanly into the existing .NET performance story. The same tools—BenchmarkDotNet, PerfView, dotnet-trace—work exactly as expected. The same optimization strategies apply.

Understanding how extension members fit into the broader .NET 10 ecosystem reveals why this feature matters beyond syntax convenience.

The Bigger Picture: C# 14 in the .NET 10 Ecosystem

Extension members arrive at a pivotal moment for the .NET platform. With .NET 10 shipping as the next Long-Term Support release, the timing positions extension members as a foundational feature for the next wave of framework and library development.

Framework Integration Points

ASP.NET Core’s middleware pipeline and dependency injection system stand to benefit immediately. The pattern of extending IServiceCollection with dozens of Add* extension methods has long been a necessary but awkward convention. Extension members enable library authors to provide coherent, discoverable APIs that feel native to the framework types they extend.

Blazor component libraries face similar opportunities. The current practice of scattering extension methods across static classes creates friction for developers trying to discover available functionality. Extension members allow component authors to present unified APIs that appear directly on framework types, improving IntelliSense discoverability and reducing cognitive load.

Implications for NuGet Package Authors

Library maintainers should start planning their migration strategies now. The transition window matters: packages that adopt extension members early gain competitive advantage through improved developer experience, but must also consider their minimum supported framework versions.

The multi-targeting story becomes critical. Packages supporting both legacy and modern .NET versions will need conditional compilation to offer extension members where available while falling back to traditional extension methods for older targets. This complexity adds maintenance burden but provides a clear upgrade path for consumers.

Pro Tip: Design your extension members with explicit interfaces in mind. The ability to add static members and properties means you can create cohesive feature surfaces that group related functionality—something impossible with scattered static methods.

Where C# Is Heading

Extension members represent a deliberate step toward more expressive composition primitives. The language team has signaled that roles and extensions—the broader feature set from which extension members emerged—remain on the roadmap. This positions C# to eventually support capabilities approaching type classes or traits, expanding what’s possible without inheritance hierarchies.

The .NET 10 ecosystem provides the foundation. Understanding extension members now prepares you for the composition-first patterns that will define idiomatic C# in the years ahead.

Key Takeaways

- Start identifying extension methods in your codebase that would benefit from extension properties—these are your first migration candidates

- Use extension members to add computed properties to DTOs and third-party types instead of creating wrapper classes

- Combine the new field keyword with extension properties to create cleaner, more expressive null-safe APIs

- Profile your extension member usage in hot paths—while usually zero-overhead, verify with BenchmarkDotNet in performance-critical code