Building a Production-Ready Rate Limiter: From Token Bucket to Distributed Redis Implementation

Your API is getting hammered. Response times are spiking, your database connection pool is exhausted, and legitimate users are getting timeouts because a single client decided to run a poorly-written batch script. You need rate limiting, but the tutorials you find either stop at toy implementations or hand-wave the distributed parts.

This guide covers the full journey: algorithm selection, Redis-backed implementation with proper atomicity, distributed coordination patterns, and the operational concerns that separate demo code from production systems. By the end, you’ll have rate limiting that actually works when your pager goes off at 3 AM.

Why Most Rate Limiting Tutorials Fail You

The standard rate limiting tutorial shows you a dictionary with timestamps and calls it a day. Then you deploy it, scale to three instances, and watch in horror as clients get 3x their intended quota. The tutorial didn’t mention that part.

The gap between textbook and production is wide. Academic descriptions of token bucket algorithms assume a single process with perfect memory. Real systems have multiple nodes, network partitions, clock drift, and clients who will exploit every inconsistency they find. The algorithm that works perfectly in a whiteboard interview falls apart the moment it encounters the chaos of distributed systems.

Consider what happens when you scale a simple in-memory rate limiter. Your application runs on one server, tracking requests in a Python dictionary. It works perfectly—every client gets exactly their allotted quota. Then traffic grows, you add a load balancer, and suddenly you have three instances. Each instance has its own dictionary, its own view of the world. A client making requests gets routed round-robin to all three, and each server thinks it’s only seeing a third of the traffic. Your carefully tuned 100 requests/minute limit becomes 300 requests/minute in practice.

Here are the failure modes that textbook implementations ignore:

Race conditions destroy your limits. Two requests arrive simultaneously at different nodes. Both check the counter, both see “49 of 50 used,” both increment, and suddenly your 50-request limit allowed 51. Multiply this by high concurrency and your limits become suggestions. Under load, you might see 10-20% overage from race conditions alone. For APIs protecting expensive resources—think GPU inference or third-party API calls with per-request costs—this overage directly translates to financial loss.

Clock skew creates unfair windows. Node A thinks it’s 12:00:00, Node B thinks it’s 12:00:03. A sliding window implementation will calculate different results on each node. Clients routed to different nodes get different treatment. In extreme cases, a client could be rejected on one node while having their full quota available on another. NTP helps, but clock drift is inevitable in distributed systems—you need to design for it, not hope it away.

Memory exhaustion is silent. Storing every request timestamp for a sliding window log works great with 100 clients. With 100,000 clients making 1,000 requests each, you’re storing 100 million timestamps. Your rate limiter just became your biggest memory consumer. Worse, memory exhaustion typically manifests as increased garbage collection pressure first, causing latency spikes that look like application bugs rather than rate limiter issues.

State persistence is overlooked. What happens when your application restarts? In-memory rate limiters lose all state. Clients who were near their limits suddenly have fresh quotas. Clients who had available quota might get rejected if the new instance starts counting from zero in a different time window. The transition behavior matters, and most tutorials don’t even acknowledge it exists.

“Distributed” means more than “uses Redis.” Pointing all your nodes at a single Redis instance solves the shared state problem but introduces new ones: Redis becomes a single point of failure, network latency adds to every request, and Redis itself needs protection from the traffic you’re trying to limit. You’ve traded one problem for several others, and now you need strategies for all of them.

Understanding these failure modes is the first step toward building rate limiting that survives contact with production traffic. The algorithms matter, but the implementation details matter more.

Token Bucket vs Sliding Window: Picking the Right Algorithm

Three algorithms dominate production rate limiting. Each makes different tradeoffs between burst tolerance, precision, and resource usage. Picking the right one depends on what you’re actually protecting.

Token Bucket: Smooth Rates with Burst Tolerance

Token bucket works like a bucket that fills with tokens at a steady rate. Each request consumes a token. If the bucket is empty, the request is rejected. The bucket has a maximum capacity, allowing bursts up to that limit.

The mental model is straightforward: imagine a bucket that can hold 200 tokens. Every second, 100 new tokens drip into the bucket. If the bucket is full, the extra tokens overflow and are lost. When a request arrives, it takes a token from the bucket. If there are no tokens, the request must wait or be rejected.

import timefrom dataclasses import dataclass

@dataclassclass TokenBucket: capacity: float # Maximum tokens (burst size) refill_rate: float # Tokens added per second tokens: float = 0.0 last_refill: float = 0.0

def __post_init__(self): self.tokens = self.capacity self.last_refill = time.monotonic()

def consume(self, tokens: int = 1) -> bool: now = time.monotonic() # Add tokens based on elapsed time elapsed = now - self.last_refill self.tokens = min(self.capacity, self.tokens + elapsed * self.refill_rate) self.last_refill = now

if self.tokens >= tokens: self.tokens -= tokens return True return False

# Allow 100 req/sec with bursts up to 200bucket = TokenBucket(capacity=200, refill_rate=100)Token bucket excels when you want to allow legitimate traffic bursts—like a mobile app syncing after coming online—while enforcing a long-term average rate. The capacity parameter controls how much burst you’ll tolerate, while the refill rate controls the sustained throughput. A capacity of 200 with a refill rate of 100 means a client can burst 200 requests instantly, then sustain 100 requests per second indefinitely.

The key insight is that token bucket separates burst behavior from average rate. You can configure aggressive burst limits while maintaining conservative average rates, or vice versa. This flexibility makes it popular for APIs where usage patterns are naturally bursty.

Sliding Window Log: Precision at a Cost

Sliding window log stores the timestamp of every request in the window. To check the limit, count timestamps within the last N seconds. This gives exact precision but costs O(n) memory per client.

import timefrom collections import dequefrom typing import Deque

class SlidingWindowLog: def __init__(self, window_seconds: int, max_requests: int): self.window = window_seconds self.limit = max_requests self.timestamps: Deque[float] = deque()

def allow(self) -> bool: now = time.monotonic() cutoff = now - self.window

# Remove expired timestamps while self.timestamps and self.timestamps[0] < cutoff: self.timestamps.popleft()

if len(self.timestamps) < self.limit: self.timestamps.append(now) return True return FalseThe precision comes from tracking every single request. There’s no approximation, no weighting—you know exactly how many requests occurred in the last N seconds. This makes sliding window log ideal for scenarios where precision matters more than efficiency: rate limiting password reset emails, SMS verification codes, or expensive API calls that cost real money.

The downside is obvious: memory usage scales linearly with request volume. A client making 1000 requests per minute requires storing 1000 timestamps. Multiply by thousands of clients and memory consumption becomes a real concern. For high-volume scenarios, this algorithm quickly becomes impractical.

Use sliding window log when precision matters more than memory—rate limiting expensive operations like password reset emails or SMS verification codes where over-allowing even a few requests has significant consequences.

Sliding Window Counter: The Practical Middle Ground

Sliding window counter approximates the sliding window using two fixed counters: the current window and the previous window. It weights the previous window’s count by how much of it overlaps with our sliding window.

import time

class SlidingWindowCounter: def __init__(self, window_seconds: int, max_requests: int): self.window = window_seconds self.limit = max_requests self.current_count = 0 self.previous_count = 0 self.current_window_start = self._get_window_start(time.time())

def _get_window_start(self, timestamp: float) -> float: return (timestamp // self.window) * self.window

def allow(self) -> bool: now = time.time() window_start = self._get_window_start(now)

# Roll over to new window if needed if window_start != self.current_window_start: self.previous_count = self.current_count self.current_count = 0 self.current_window_start = window_start

# Calculate weighted count elapsed_in_window = now - window_start weight = 1 - (elapsed_in_window / self.window) estimated_count = self.current_count + (self.previous_count * weight)

if estimated_count < self.limit: self.current_count += 1 return True return FalseThe approximation works because traffic patterns are typically consistent across adjacent windows. If a client made 80 requests in the previous minute, they probably made roughly 80 requests in any arbitrary 60-second sliding window that overlaps with it. The weighted average smooths over the boundary between fixed windows, eliminating the “reset rush” problem where clients exploit window boundaries.

The error bound is well-understood: worst case, you might allow up to 2x the limit at the exact moment windows transition, but only if traffic was perfectly concentrated at window edges—a pattern that rarely occurs naturally.

Sliding window counter uses O(1) memory per client while providing good-enough precision for most use cases. This is the algorithm to reach for first.

Decision Matrix

| Requirement | Best Algorithm |

|---|---|

| Allow traffic bursts | Token Bucket |

| Exact precision required | Sliding Window Log |

| High client count, memory constrained | Sliding Window Counter |

| Simple implementation | Fixed Window (not covered—too imprecise) |

For most production scenarios, sliding window counter wins. It balances precision, memory efficiency, and implementation complexity. The rest of this guide focuses on making it production-ready.

Building a Redis-Backed Sliding Window Counter

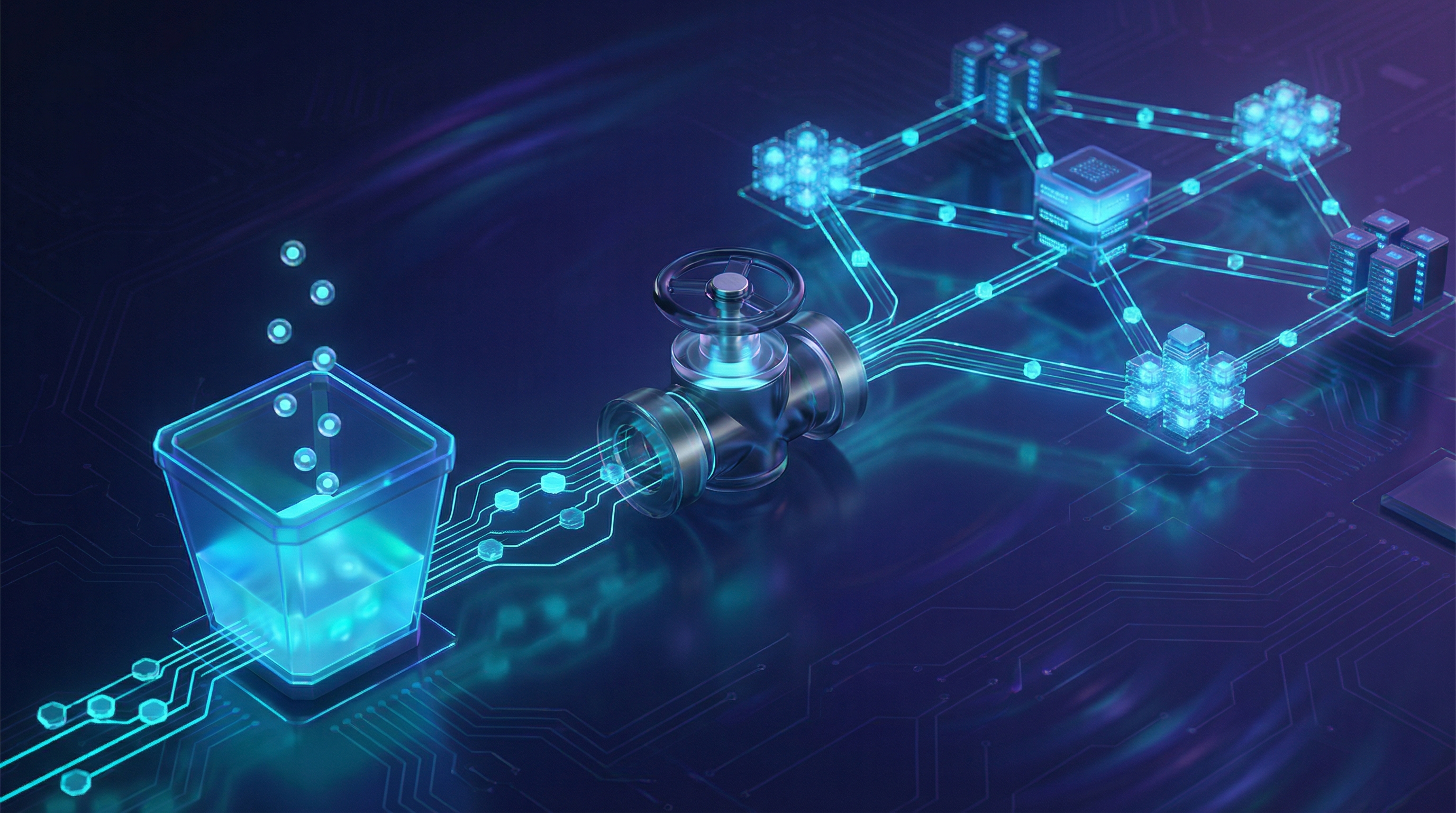

Local rate limiting breaks the moment you scale past one instance. Redis gives you shared state, but naive Redis implementations introduce race conditions. The solution is Lua scripts that execute atomically on the Redis server.

The Race Condition Problem

Consider this non-atomic sequence:

- Request A reads counter: 49

- Request B reads counter: 49

- Request A increments: 50

- Request B increments: 51 (limit exceeded)

Both requests saw 49 and assumed they could proceed. This happens constantly under load. The window of vulnerability might only be microseconds, but at thousands of requests per second, microsecond windows get hit frequently.

You can’t solve this with application-level locking. Distributed locks are slow and introduce their own failure modes. Redis transactions (MULTI/EXEC) don’t help either—they only guarantee atomicity of writes, not read-then-write operations. By the time your EXEC runs, another client might have modified the value you read.

Atomic Operations with Lua Scripts

Redis executes Lua scripts atomically—no other commands run until the script completes. Here’s a sliding window counter that can’t race:

import redisimport timefrom typing import Tuple

class RedisRateLimiter: """ Sliding window counter rate limiter using Redis. All operations are atomic via Lua scripting. """

# Lua script for atomic rate limit check and increment LUA_SCRIPT = """ local key = KEYS[1] local window = tonumber(ARGV[1]) local limit = tonumber(ARGV[2]) local now = tonumber(ARGV[3])

-- Calculate window boundaries local window_start = math.floor(now / window) * window local previous_window_start = window_start - window

local current_key = key .. ':' .. window_start local previous_key = key .. ':' .. previous_window_start

-- Get counts from both windows local current_count = tonumber(redis.call('GET', current_key) or '0') local previous_count = tonumber(redis.call('GET', previous_key) or '0')

-- Calculate weighted count local elapsed = now - window_start local weight = 1 - (elapsed / window) local weighted_count = current_count + (previous_count * weight)

if weighted_count >= limit then -- Calculate when the client can retry local retry_after = window - elapsed return {0, math.ceil(weighted_count), retry_after, limit - math.ceil(weighted_count)} end

-- Increment current window and set TTL redis.call('INCR', current_key) redis.call('EXPIRE', current_key, window * 2)

return {1, math.ceil(weighted_count) + 1, 0, limit - math.ceil(weighted_count) - 1} """

def __init__(self, redis_client: redis.Redis, window_seconds: int = 60, limit: int = 100): self.redis = redis_client self.window = window_seconds self.limit = limit self._script = self.redis.register_script(self.LUA_SCRIPT)

def check(self, identifier: str) -> Tuple[bool, dict]: """ Check if request is allowed and update counter atomically.

Returns: (allowed, metadata) where metadata contains: - count: current request count in window - retry_after: seconds until next allowed request (if rejected) - remaining: requests remaining in window """ key = f"ratelimit:{identifier}" now = time.time()

result = self._script( keys=[key], args=[self.window, self.limit, now] )

allowed, count, retry_after, remaining = result return bool(allowed), { "count": count, "retry_after": retry_after if not allowed else 0, "remaining": max(0, remaining), "limit": self.limit, "window": self.window }The Lua script reads both window counters, calculates the weighted count, and conditionally increments—all atomically. No race conditions possible. The script registration via register_script is important: it caches the script’s SHA hash, avoiding the overhead of sending the full script text on every call.

Notice the key expiration strategy: we set TTL to window * 2. This ensures the previous window’s counter remains available for the weighted calculation while still cleaning up old keys automatically. Without this, you’d accumulate keys forever.

Key Design for Multi-Tenant Rate Limiting

The key structure ratelimit:{identifier}:{window_start} supports multiple limiting strategies:

def build_key(request) -> str: """Build rate limit key based on strategy."""

# Per-IP limiting (anonymous users) if not request.user: return f"ip:{request.client_ip}"

# Per-user limiting (authenticated) if request.api_key: return f"apikey:{request.api_key}"

# Per-user + endpoint limiting return f"user:{request.user_id}:endpoint:{request.path}"The key structure directly encodes your rate limiting policy. Want per-endpoint limits? Include the endpoint in the key. Want to limit authenticated and anonymous users separately? Use different prefixes. Want to implement tiered limits? The key tells you which tier’s limits to apply.

💡 Pro Tip: Combine strategies with different limits. Apply a loose per-IP limit to catch scrapers, then a tighter per-user limit for authenticated traffic. A request must satisfy both limits to proceed. This defense-in-depth approach catches more abuse patterns than any single strategy.

Handling Redis Failures

Redis will fail. Network partitions happen. Failovers cause brief unavailability. Your rate limiter must have a plan:

import loggingfrom redis.exceptions import RedisError

class ResilientRateLimiter: def __init__(self, limiter: RedisRateLimiter, fail_open: bool = True): self.limiter = limiter self.fail_open = fail_open self.logger = logging.getLogger(__name__)

def check(self, identifier: str) -> Tuple[bool, dict]: try: return self.limiter.check(identifier) except RedisError as e: self.logger.error(f"Redis error in rate limiter: {e}")

if self.fail_open: # Allow request but flag it return True, {"fallback": True, "remaining": -1} else: # Reject request when Redis is down return False, {"fallback": True, "retry_after": 60}Fail-open keeps your service available but removes protection. Fail-closed maintains protection but causes outages when Redis has issues. Choose based on what you’re protecting—authentication endpoints might fail-closed while read-heavy APIs fail-open.

The choice isn’t binary. You might fail-closed for the first few seconds of an outage, then switch to fail-open with degraded local limits if Redis doesn’t recover. The key is making an explicit decision rather than letting Redis errors propagate as 500 errors to your users.

The Distributed Rate Limiting Problem

A single Redis instance handles most scenarios, but at scale it becomes a bottleneck. Every request requires a Redis round-trip, adding latency and concentrating load. The solution is a hybrid approach: local rate limiting with periodic global synchronization.

Why Eventual Consistency Works

Rate limiting doesn’t need perfect accuracy. If your limit is 1000 requests/minute, allowing 1050 during a synchronization delay is acceptable. What matters is preventing order-of-magnitude violations.

The insight is that rate limits are already approximate. A “100 requests per minute” limit doesn’t mean exactly 100—it means “roughly 100, plus or minus.” The precision that would require perfect global coordination isn’t worth the latency and complexity cost. Eventual consistency gives you 90% of the protection at 10% of the cost.

This is a different mindset than database transactions, where partial consistency can corrupt data. Rate limiting is about load protection, and load protection is inherently statistical. Your servers don’t care if they receive 1000 or 1050 requests—they care about the difference between 1000 and 10000.

Synchronization Strategies: Centralized vs Gossip-Based

There are two main approaches to keeping nodes synchronized:

Centralized synchronization uses Redis (or another shared store) as the source of truth. Nodes periodically push their local counts to Redis and pull the global state. This is simpler to implement and reason about, but creates a dependency on Redis availability for accuracy (though not for basic functionality if you implement proper fallbacks).

Gossip-based synchronization has nodes communicate directly with each other, sharing their local counts and converging on a global view. This eliminates the Redis dependency but adds complexity: you need service discovery, peer-to-peer communication, and convergence algorithms. It’s rarely worth it unless you have specific requirements that preclude centralized coordination.

For most applications, centralized synchronization with Redis is the right choice. The complexity of gossip protocols only pays off at extreme scale.

The Local + Global Hybrid Approach

Each node maintains local counters and periodically syncs with Redis. Between syncs, nodes enforce limits locally using their share of the global quota.

import asyncioimport timefrom typing import Dictfrom dataclasses import dataclass, field

@dataclassclass LocalCounter: count: int = 0 last_sync: float = field(default_factory=time.time)

class HybridRateLimiter: """ Local + global rate limiting to reduce Redis round trips. Each node gets a fraction of the global limit and syncs periodically. """

def __init__( self, redis_limiter: RedisRateLimiter, node_count: int = 4, sync_interval: float = 1.0 ): self.redis_limiter = redis_limiter self.node_count = node_count self.sync_interval = sync_interval self.local_limit = redis_limiter.limit // node_count self.local_counters: Dict[str, LocalCounter] = {} self._sync_task = None

def _get_local_counter(self, identifier: str) -> LocalCounter: if identifier not in self.local_counters: self.local_counters[identifier] = LocalCounter() return self.local_counters[identifier]

async def check(self, identifier: str) -> Tuple[bool, dict]: counter = self._get_local_counter(identifier) now = time.time()

# Check if we need to sync with global state if now - counter.last_sync > self.sync_interval: allowed, metadata = self.redis_limiter.check(identifier) counter.count = 0 counter.last_sync = now return allowed, metadata

# Enforce local limit between syncs if counter.count >= self.local_limit: # Local limit hit—check global to be sure allowed, metadata = self.redis_limiter.check(identifier) counter.count = 0 counter.last_sync = now return allowed, metadata

# Allow locally and increment counter.count += 1 return True, { "count": counter.count, "remaining": self.local_limit - counter.count, "local": True }

async def start_background_sync(self): """Periodically sync all local counters to Redis.""" async def sync_loop(): while True: await asyncio.sleep(self.sync_interval) for identifier, counter in list(self.local_counters.items()): if counter.count > 0: # Batch sync to Redis self.redis_limiter.check(identifier) counter.count = 0 counter.last_sync = time.time()

self._sync_task = asyncio.create_task(sync_loop())This reduces Redis calls dramatically. With 4 nodes and a 1-second sync interval, you go from 1000 Redis calls/second to roughly 4 calls/second for a single client. The tradeoff is reduced precision during the sync interval, but as discussed, this precision loss is acceptable for most rate limiting use cases.

The node_count parameter requires coordination—all nodes must agree on how many nodes exist. In practice, you’d either configure this statically or derive it from service discovery.

Handling Network Partitions

When a node can’t reach Redis, it must decide: stop accepting requests, or continue with local-only limiting?

async def check_with_partition_handling(self, identifier: str) -> Tuple[bool, dict]: counter = self._get_local_counter(identifier)

try: # Try global check allowed, metadata = await self._check_global(identifier) counter.last_successful_sync = time.time() return allowed, metadata except RedisError: # Partition detected—use conservative local limiting partition_duration = time.time() - counter.last_successful_sync

if partition_duration > 60: # Extended partition—be very conservative emergency_limit = self.local_limit // 4 else: emergency_limit = self.local_limit // 2

if counter.partition_count >= emergency_limit: return False, {"partition": True, "retry_after": 5}

counter.partition_count += 1 return True, {"partition": True, "degraded": True}The strategy progressively tightens limits as the partition extends. Short partitions might just be Redis failover—keep serving with slightly reduced capacity. Extended partitions suggest a real problem—reduce capacity significantly to protect your backend.

⚠️ Warning: During partitions, total system capacity equals

emergency_limit × node_count. Size your emergency limits so this sum doesn’t exceed what your backend can handle. If your backend can handle 1000 req/sec and you have 4 nodes, each node’s emergency limit should be well under 250.

Rate Limiting as Middleware: Express and FastAPI Examples

Rate limiting belongs in middleware, not scattered through business logic. Here are production-ready implementations for the two most common backend frameworks.

Express Middleware (TypeScript)

import { Request, Response, NextFunction } from 'express';import Redis from 'ioredis';

interface RateLimitConfig { windowSeconds: number; limit: number; keyGenerator?: (req: Request) => string;}

interface RateLimitInfo { allowed: boolean; remaining: number; resetTime: number; retryAfter?: number;}

const LUA_SCRIPT = `local key = KEYS[1]local window = tonumber(ARGV[1])local limit = tonumber(ARGV[2])local now = tonumber(ARGV[3])

local window_start = math.floor(now / window) * windowlocal previous_window_start = window_start - window

local current_key = key .. ':' .. window_startlocal previous_key = key .. ':' .. previous_window_start

local current_count = tonumber(redis.call('GET', current_key) or '0')local previous_count = tonumber(redis.call('GET', previous_key) or '0')

local elapsed = now - window_startlocal weight = 1 - (elapsed / window)local weighted_count = current_count + (previous_count * weight)

if weighted_count >= limit then local retry_after = window - elapsed return {0, math.ceil(weighted_count), retry_after, window_start + window}end

redis.call('INCR', current_key)redis.call('EXPIRE', current_key, window * 2)

return {1, math.ceil(weighted_count) + 1, 0, window_start + window}`;

export function createRateLimiter(redis: Redis, config: RateLimitConfig) { const { windowSeconds, limit, keyGenerator } = config;

const getKey = keyGenerator ?? ((req: Request) => { // Default: use API key if present, otherwise IP const apiKey = req.headers['x-api-key'] as string; return apiKey ? `apikey:${apiKey}` : `ip:${req.ip}`; });

return async (req: Request, res: Response, next: NextFunction) => { const identifier = getKey(req); const key = `ratelimit:${identifier}`; const now = Date.now() / 1000;

try { const result = await redis.eval( LUA_SCRIPT, 1, key, windowSeconds, limit, now ) as [number, number, number, number];

const [allowed, count, retryAfter, resetTime] = result; const remaining = Math.max(0, limit - count);

// Always set rate limit headers res.setHeader('X-RateLimit-Limit', limit); res.setHeader('X-RateLimit-Remaining', remaining); res.setHeader('X-RateLimit-Reset', Math.ceil(resetTime));

if (!allowed) { res.setHeader('Retry-After', Math.ceil(retryAfter)); return res.status(429).json({ error: 'Too Many Requests', message: `Rate limit exceeded. Try again in ${Math.ceil(retryAfter)} seconds.`, retryAfter: Math.ceil(retryAfter) }); }

next(); } catch (error) { // Fail open on Redis errors console.error('Rate limiter error:', error); next(); } };}

// Usage with different limits per routeexport function rateLimitByRoute(redis: Redis) { return { standard: createRateLimiter(redis, { windowSeconds: 60, limit: 100 }), strict: createRateLimiter(redis, { windowSeconds: 60, limit: 10 }), relaxed: createRateLimiter(redis, { windowSeconds: 60, limit: 1000 }) };}FastAPI Middleware (Python)

The Python equivalent using FastAPI’s dependency injection pattern provides clean separation:

from fastapi import FastAPI, Request, HTTPException, Dependsfrom fastapi.responses import JSONResponsefrom typing import Callable, Optionalimport redis.asyncio as redis

class RateLimitMiddleware: def __init__(self, redis_url: str, window: int = 60, limit: int = 100): self.redis = redis.from_url(redis_url) self.window = window self.limit = limit self._script_sha = None

async def _ensure_script(self): if self._script_sha is None: self._script_sha = await self.redis.script_load(LUA_SCRIPT) return self._script_sha

def __call__(self, key_func: Optional[Callable] = None): async def dependency(request: Request): identifier = key_func(request) if key_func else request.client.host sha = await self._ensure_script()

result = await self.redis.evalsha( sha, 1, f"ratelimit:{identifier}", self.window, self.limit, time.time() )

allowed, count, retry_after, remaining = result request.state.rate_limit = { "limit": self.limit, "remaining": max(0, remaining), "reset": time.time() + (self.window - retry_after) }

if not allowed: raise HTTPException( status_code=429, detail=f"Rate limit exceeded. Retry after {retry_after:.0f} seconds.", headers={"Retry-After": str(int(retry_after))} )

return Depends(dependency)The dependency injection pattern keeps rate limiting logic out of your endpoint handlers entirely. You declare the dependency, and FastAPI handles the rest.

Applying Different Limits to Different Endpoints

import express from 'express';import Redis from 'ioredis';import { rateLimitByRoute } from './rateLimitMiddleware';

const app = express();const redis = new Redis(process.env.REDIS_URL);const limiters = rateLimitByRoute(redis);

// Strict limiting on auth endpointsapp.post('/api/auth/login', limiters.strict, authController.login);app.post('/api/auth/reset-password', limiters.strict, authController.resetPassword);

// Standard limiting on most endpointsapp.use('/api', limiters.standard);

// Relaxed limiting on read-heavy endpointsapp.get('/api/public/catalog', limiters.relaxed, catalogController.list);The pattern extends naturally. You can create limiters for specific use cases—signup flows, webhook receivers, internal service calls—each with appropriate limits.

Proper HTTP Response Headers

The X-RateLimit-* headers follow the IETF draft standard:

| Header | Description |

|---|---|

X-RateLimit-Limit | Maximum requests allowed in window |

X-RateLimit-Remaining | Requests remaining in current window |

X-RateLimit-Reset | Unix timestamp when window resets |

Retry-After | Seconds until client should retry (only on 429) |

📝 Note: Always include

Retry-Afteron 429 responses. Well-behaved clients use this to back off automatically, reducing retry storms. Without this header, clients guess—and they usually guess wrong, hammering your API repeatedly.

Good client libraries exponential backoff with jitter. Your Retry-After header gives them a starting point, but expect some clients to ignore it entirely. Your rate limiter needs to handle clients that don’t cooperate, which is why proper enforcement matters more than proper headers.

Production Hardening: Monitoring, Alerts, and Edge Cases

A rate limiter without monitoring is a liability. You need visibility into whether it’s working, how much overhead it adds, and early warning when something’s wrong.

Metrics That Matter

Track these metrics and export them to your monitoring system:

import timefrom prometheus_client import Counter, Histogram, Gauge

# Request outcomesrate_limit_allowed = Counter( 'rate_limit_allowed_total', 'Requests allowed by rate limiter', ['identifier_type', 'endpoint'])

rate_limit_rejected = Counter( 'rate_limit_rejected_total', 'Requests rejected by rate limiter', ['identifier_type', 'endpoint'])

# Latency overheadrate_limit_latency = Histogram( 'rate_limit_check_duration_seconds', 'Time spent checking rate limits', buckets=[0.001, 0.005, 0.01, 0.025, 0.05, 0.1])

# Redis healthredis_connection_errors = Counter( 'rate_limit_redis_errors_total', 'Redis connection errors in rate limiter')

rate_limit_fallback_active = Gauge( 'rate_limit_fallback_active', 'Whether rate limiter is in fallback mode')

class InstrumentedRateLimiter: def __init__(self, limiter: RedisRateLimiter): self.limiter = limiter

def check(self, identifier: str, endpoint: str = "default") -> Tuple[bool, dict]: id_type = "apikey" if identifier.startswith("apikey:") else "ip"

with rate_limit_latency.time(): try: allowed, metadata = self.limiter.check(identifier)

if allowed: rate_limit_allowed.labels(id_type, endpoint).inc() else: rate_limit_rejected.labels(id_type, endpoint).inc()

rate_limit_fallback_active.set(0) return allowed, metadata

except Exception as e: redis_connection_errors.inc() rate_limit_fallback_active.set(1) raiseThe cardinality of your labels matters. Using the full endpoint path or client identifier as a label will explode your metric storage. Stick to low-cardinality dimensions: identifier type, endpoint category, and similar groupings.

Alert Thresholds

Set alerts before problems become outages:

| Metric | Warning | Critical |

|---|---|---|

| p99 latency | > 10ms | > 50ms |

| Rejection rate | > 5% | > 20% |

| Redis error rate | > 0.1% | > 1% |

| Fallback mode | Any activation | > 1 minute |

These thresholds are starting points. Tune them based on your traffic patterns and SLOs. A 5% rejection rate might be normal during a product launch and alarming during quiet periods.

Handling Clock Drift

Distributed systems have clock drift. Your rate limiter needs to tolerate it:

import time

def get_tolerant_window_start(now: float, window: int, tolerance: float = 0.5) -> float: """ Calculate window start with tolerance for clock drift. Tolerance is the maximum expected drift as a fraction of window size. """ window_start = (now // window) * window

# If we're very close to a window boundary, use the previous window # to avoid edge cases from clock drift between nodes elapsed = now - window_start if elapsed < (window * tolerance): # We might be in a new window on this node but old window on others # Use a slightly higher weight for the previous window pass

return window_startA simpler approach: use Redis TIME command instead of local time. All nodes see the same clock, eliminating drift entirely at the cost of one extra Redis call. For high-precision requirements, this overhead is worth it. For most applications, NTP-synchronized clocks with some tolerance in your window calculations is sufficient.

Graceful Degradation Patterns

Build degradation into your rate limiter from day one:

from enum import Enum

class DegradationLevel(Enum): NORMAL = "normal" # Full Redis-backed limiting DEGRADED = "degraded" # Local-only with conservative limits EMERGENCY = "emergency" # Minimal limiting, log everything DISABLED = "disabled" # No limiting (last resort)

class AdaptiveRateLimiter: def __init__(self, redis_limiter, local_limiter): self.redis = redis_limiter self.local = local_limiter self.level = DegradationLevel.NORMAL self.consecutive_failures = 0

async def check(self, identifier: str) -> Tuple[bool, dict]: if self.level == DegradationLevel.DISABLED: return True, {"degradation": "disabled"}

if self.level == DegradationLevel.EMERGENCY: # Log everything, minimal limiting return self.local.check(identifier)

try: result = await self.redis.check(identifier) self.consecutive_failures = 0 self._maybe_recover() return result except Exception: self.consecutive_failures += 1 self._maybe_degrade() return self.local.check(identifier)

def _maybe_degrade(self): if self.consecutive_failures > 10: self.level = DegradationLevel.EMERGENCY elif self.consecutive_failures > 3: self.level = DegradationLevel.DEGRADED

def _maybe_recover(self): if self.level != DegradationLevel.NORMAL: self.level = DegradationLevel.NORMALThe degradation ladder gives you options. Instead of binary “working/broken,” you have gradual reduction in protection that matches gradual infrastructure problems. Recovery should be automatic but conservative—don’t flip back to NORMAL on a single success.

Beyond Basic Rate Limiting: Adaptive and Tiered Strategies

Basic rate limiting treats all requests equally. Real systems need more nuance: different limits for different customers, adaptive responses to system load, and intelligent queuing instead of hard rejections.

Per-User vs Per-API-Key vs Per-IP

Layer multiple limiting strategies for defense in depth:

| Strategy | Protects Against | Typical Limit |

|---|---|---|

| Per-IP | Unauthenticated abuse, DDoS | 100/min |

| Per-API-Key | Individual client overuse | 1000/min |

| Per-User | Account-level abuse | 500/min |

| Per-Endpoint | Protecting expensive operations | 10/min |

| Global | Overall system capacity | 50000/min |

Apply multiple limits simultaneously. A request passes only if it satisfies all applicable limits. This catches abuse patterns that any single strategy would miss: a malicious user creating multiple API keys, multiple users sharing an IP at a corporate office, or a single user hammering an expensive endpoint.

Tiered Limits for Different Plans

SaaS products need different limits for different pricing tiers:

┌─────────────────┐ ┌─────────────────┐ ┌─────────────────┐│ Free Tier │ │ Pro Tier │ │ Enterprise ││ 100 req/min │ │ 1000 req/min │ │ 10000 req/min ││ No burst │ │ 2x burst │ │ 5x burst │└─────────────────┘ └─────────────────┘ └─────────────────┘Store tier limits in your user database and look them up at request time. Cache aggressively—tier changes are infrequent. A common pattern is caching tier information for 5-15 minutes, accepting that a user who upgrades might not see increased limits immediately. For most applications, this latency is acceptable and dramatically reduces database load.

Adaptive Rate Limiting

When your system is under stress, tighten limits automatically:

- Monitor system health (CPU, memory, response latency, error rate)

- Define thresholds for “healthy,” “stressed,” and “critical”

- Reduce limits proportionally as health degrades

- Restore limits gradually as health recovers

This prevents cascade failures: instead of letting traffic overwhelm your system until it crashes, you shed load gracefully. The key is that reduction must be automatic and fast—by the time a human notices the problem, the cascade has already started.

Implementation typically involves a background process that monitors system metrics and adjusts a global “load factor” that all rate limiters read. A load factor of 1.0 means normal limits; 0.5 means half the normal limits. The adjustment should be fast on the way down (seconds) and slow on the way up (minutes) to prevent oscillation.

Queuing Instead of Rejection

For some use cases, queuing beats rejection. If a client exceeds their rate limit but the request is important (webhook delivery, payment processing), queue it for later execution instead of returning 429.

The tradeoff is complexity: you need a queue, workers, and handling for queue overflow. But for critical paths, it’s worth it. A queued webhook that arrives 30 seconds late is vastly better than a rejected webhook that the sender must retry manually.

Implement queuing selectively. Read requests should never be queued—stale reads are worse than rejected reads. Write requests that are idempotent and time-insensitive are good candidates. Payment callbacks, event notifications, and data exports often benefit from queuing.

Key Takeaways

-

Use sliding window counters with Redis Lua scripts for most production scenarios—they balance precision, memory efficiency, and atomicity without the complexity of more exotic algorithms.

-

Implement a hybrid local-global rate limiting strategy to reduce Redis round trips while maintaining accuracy across distributed nodes—this can cut Redis calls by 99% for high-traffic clients.

-

Always include X-RateLimit-Remaining and Retry-After headers so clients can self-throttle instead of hammering your retry logic—well-behaved clients will back off automatically.

-

Set up monitoring for rate limiter overhead (p99 latency) and rejection rates before you need them—these metrics are your early warning system for both rate limiter problems and legitimate traffic spikes.

-

Build graceful degradation into your rate limiter from day one: decide whether to fail-open or fail-closed when Redis is unreachable, and implement multiple degradation levels for different failure scenarios.